|

The Bourne

Castle excavations of 1861

The archaeological dig of 1861 was not

intended as a serious excavation of the site but rather as a sideshow or

entertainment for delegates and visitors to the annual meeting of the Lincoln

Diocesan Architectural Society.

The organisation represented many people with interests in their heritage and

annual meetings were rotated to various towns around the county. In the summer

of that year, Bourne was chosen as the host venue, due mainly to the

enthusiasm and encouragement of one of its members, Robert Mason Mills, founder

of the town’s aerated water business and a dedicated antiquarian who was deeply

fascinated by the history of the locality.

On Monday 8th April 1861, the Rev Edward Trollope, the society’s honorary

secretary who was organising the event, visited Bourne to make the preliminary

arrangements and to select various sites for the members to visit. These

included Bourne Abbey, the ruins of the Valli Dei (Vaudey) Cistercian Abbey in

the grounds of Grimsthorpe Park, the temple of the Hospitaller Knights at

Aslackby and the site of Bourne Castle. Unfortunately, the only remains of the

latter were a few bumps and hillocks in the field off South Street and so it was

arranged that a superficial dig would begin as an added attraction although it

would appear that this would consist of nothing more than lifting off the

surface soil in an attempt to reveal the foundations or any remaining stonework,

if indeed it did exist.

The society could not afford detailed excavations and neither were they planned

and it was intended that the search would take place only over a few days to

coincide with the meeting which was fixed for Wednesday and Thursday, 5th and 6th June 1861.

By Saturday 11th May, a working committee had been appointed and was busy

finalising the itinerary, the prospect of the castle excavations now exciting

great interest because at that time its reputation as the home of Saxon kings

Morcar, Oslac and Leofric, was well known although the more famous connection

with Hereward the Wake was not popularised until five years later when Charles

Kinglsey wrote his famous novel in 1866, basing his account on the romantic

tales recounted in certain mediaeval chronicles, suggesting that he was the son

of the Earl of Leofric and his wife Lady Godiva who owned the manor of Bourne

and the castle in the Wellhead field which became known as Hereward's

birthplace.

By this time, the itinerary for the visit was becoming extensive and more people

were co-opted on to the organising committee which then formed two separate

sub-committees, one to superintend the arrangements at the Town Hall from where

the events would be directed, and the other to take over the management of the

railway goods warehouse in South Street which the railway company had agreed

could

be converted for use as a museum and lecture hall and it was also within easy

reach of the site of the proposed excavations. By this time, the programme for

the two-day event had been provisionally drawn up and it was so varied and

interesting that a large gathering was anticipated.

The local Rifle Corps was recruited to hold a parade through the town on the

first day, Wednesday, and after marching to the Abbey Church for a service,

everyone gathered at the castle site for a lecture on its history, although

admission was by ticket only. There was a brass band to provide music and

visitors later moved to the temporary museum to inspect the displays and hear

lectures on various topics. There was a

public tea that day and a dinner on the Thursday and as the organisers

anticipated, the events on both days were crowded.

Excursions were arranged for visitors to see all of the important sites and

historic buildings in

Bourne and the surrounding villages using a succession of horse-drawn carriages

leaving at regular intervals and all were busy throughout the two days. The tour

on Wednesday took in the north of Bourne, including Dunsby, Dowsby, Sempringham,

Billingborough, Horbling, Threekingham, Folkingham (where there was a stop of 20

minutes to inspect the remains of the Aslackby Preceptory), Rippingale, Haconby

and Morton. On Thursday the route took visitors south though Thurlby, Baston,

Langtoft, Market Deeping, Northborough, Peakirk, Crowland and Deeping St James.

Excavations on the castle site had begun on Monday 27th May and the only

objective was to lay bare some of the foundations and it is therefore worth

remembering that the team for this examination of an important archaeological

site consisted of little more than a few men with shovels. When the event was

over, the soil was replaced and a report on their progress drawn up. It said:

“Nearly half the moat which surrounded the castle on the south side is still in

existence. On the west side of the field, and close to the inner edge of the

moat, the workmen discovered a substantially built wall, about four feet thick,

which is supposed to have been the place where the drawbridge stood at the time

the castle was occupied.”

The committee decided that this was insufficient and so they commissioned a more

extensive and imaginative report on what they had found, suggesting that the remains of two circular

towers had been uncovered, a short distance to the west of the earthen mound

that can still be seen in the Wellhead Gardens. The report said that the walls of these towers were at least three

feet thick and the distance between them 16 feet 6 inches and that the towers formed the gatehouse to the inner bailey, or courtyard, in which

stood the keep on the mound of earth. The dig also revealed timbers in a sunken

chamber near the gatehouse and these were thought to be part of the leverage for

raising the drawbridge over the moat that surrounded the inner bailey. Opposite

the gatehouse, below the soil, were the remains of a wall that may have served

as the support of the drawbridge when let down and if this was correct, then the

moat would have been 44 feet wide at this point.

To complete their reconstruction of the castle,

the archaeologists of 1861 suggested that an outer bailey covered an area of

about eight acres and was bounded by St Peter's Pool and the course of the

Bourne Eau, right round from the pool to what is now South Street, and so a

second or outer moat was created. The keep was therefore protected, on the south

by a single moat running close beside it, and on the other three sides by two

moats, one fairly close by and the other at some distance, the latter being in fact the river itself.

All of these features have been mentioned by previous historians but none

verified by archaeological evidence.

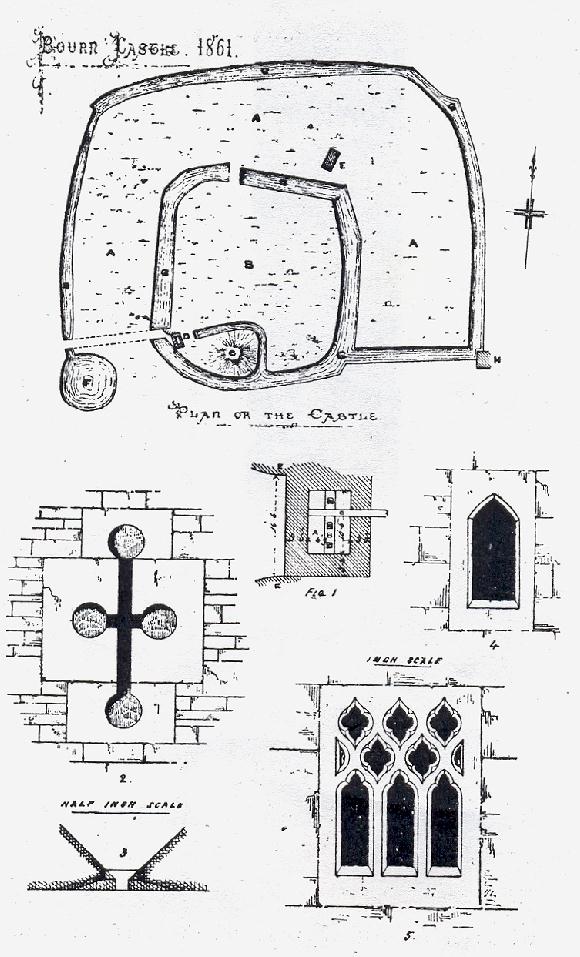

One further fact was noted in 1861: that certain stones that were built into the end of a nearby barn were the exterior parts of crossbow slits that had once been part of the castle walls. These stones can still be seen today in what is now the Shippon

Barn that stands close to the footpath across the Wellhead Gardens but their

provenance is suspect, the stone, particularly in the so-called crossbow slits,

having little appearance of the age required to fit this theory.

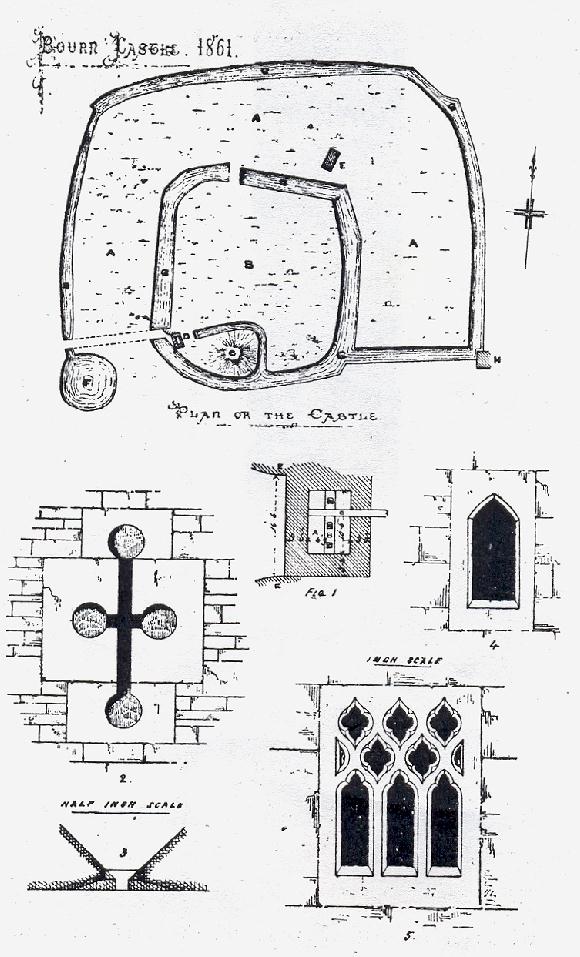

A plan of the castle by James Fowler, based on a drawing by a

local enthusiast, Robert Parker of Morton, has subsequently been used by local

historians as proof that a castle existed at this point but the reconstruction

of the layout of the entire building appears to have been inspired by the 1861

excavations. The conclusions were also given some credence when

members of the Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire Architectural Society visited

Bourne in 1889. Shortly before their arrival, some of the remains, purportedly the gatehouse,

had been laid bare for their inspection and the outline of a round tower was

discernible and it was presumed that the other tower had also existed, as was

stated in 1861, but the timbers for raising the drawbridge had apparently been

lost.

No other evidence is available as to the

existence of a castle in Bourne. The site in the Wellhead Gardens is now a scheduled ancient monument but there have been suggestions in recent years that further excavations should be carried out in an attempt to throw more light on the origins of the castle

and to lay to rest the various myths and legends that surround it. Whatever is found could then be developed as a tourist attraction and educational resource but the

trustees of the Bourne United Charities which owns the land have refused such permission and are opposed to any further excavations.

A long dry spell during the summer of 2005

revealed evidence of human occupation on the parkland where a combination of close

mowing and a lack of rain produced a large number of circular patches of bare

earth where the grass had died through lack of moisture, clearly showing the

outline of a large building or buildings that once stood on the spot. A second

set of patches also appeared to the west and these were thought to indicate

another important structure.

There was a similar occurrence during drought conditions in August 1990 but the

latest manifestation was far more detailed and welcomed as an indication of the

exact location of Bourne Castle. In the middle of it all stood a silver birch,

planted 30 years ago but still stunted in growth because it had never reached

the maturity of other trees in the vicinity that were planted at the same time,

perhaps indicating low soil levels on top of stone that had caused the grass to

die off in patches while the surrounding area remained green.

It is a romantic idea to believe that the signs revealed by the dry weather

could be evidence of the castle but it is part of Bourne’s history and that is

how the discoveries will most probably be regarded. Cyril Holdcroft, who

lives nearby in South Street, was in no doubt about their provenance and

optimistic that they were evidence of the existence of a castle. “The patches

indicate where the towers were situated and this is exciting because until now

it was not known exactly where it was located,” he said.

Mr Holdcroft, aged 84, a retired cabin services director with British Airways

who has lived in Bourne since 1939, was convinced that a detailed aerial survey

followed by an archaeological dig would produce firm evidence of the stone walls

of the castle, parts of it, perhaps the top sections of the battlements, so

close to the surface that the grass had dried up and died during long spells

without rain. This theory was fanciful because it is doubtful if a castle with

high walls would sink so low into the earth and even if it did, the patches

would be square rather than round and so a more rational explanation is post

holes from the houses and other buildings of the community that once lived here.

The existence of a castle in Bourne is however deeply embedded in the perception of the public who love their heroes and legends, even if their origins are in doubt. The 1970 opinion of

local historian J D Birkbeck therefore still stands: "Until fresh information about the origins of Bourne Castle is forthcoming, many questions will have to remain unanswered."

|

THE 1861 REPORT ON BOURNE CASTLE |

|

|

|

The archaeological report of 1861 was the

first recorded examination of the site and tradition owes much to this

impression compiled by James Fowler from a drawing by a local

enthusiast, Robert Parker, of Morton, but whether it bears any

relationship to Bourne Castle remains a matter of conjecture.

This plan was reproduced by J J Davies in his book Historic Bourne,

published in 1909, and has been used since as evidence for the

existence of a castle although little further research has been carried

out on the subject. |

WRITTEN AUGUST 2005

See also

Bourne Castle - fact or fiction

The Lincoln Diocesan

Architectural Society meeting of 1861

Return to Bourne

Castle

Go to:

Main Index

|