|

Agriculture

The main occupation in the Bourne area now and in centuries past has been farming and the effects of it. The town is surrounded by rich agricultural land, much of it reclaimed from the sea through a complicated system of fen drainage, and when land comes on the market it invariably fetches among the highest prices in Britain.

Crops have been various over the years but one has predominated and that is wheat that has been grown here for 2,000 years and no doubt before that, although the variety we see today would be totally unknown to our ancestors. There is evidence that some form of agriculture was practised by the local inhabitants during Roman times to the east of

Bourne, corn growing for instance on the reclaimed parts of the fens and on the higher ground to the west, and most probably some cattle and sheep rearing where there were breaks in the woodland that extended over most of the area at that time.

During the Anglo-Saxon period when a small settlement existed here, the main occupation would have been agriculture with each

ceorl or peasant owning that land which supported him and although he usually farmed the soil on a self-help basis, there was no common ownership of arable or meadow land. It is likely that the open field system of farming had come into existence as early as the 7th century, each being divided into furlongs that included the selions [measures of land of indeterminate area] or strips of different owners, scattered about over the various fields.

At the time of the Norman Conquest in 1066, the settlement of Bourne was similar to that in other parts of England with tofts and crofts clustered around a church together with the small homes of the people with the house or castle of the lord of the manor close by. The tofts contained the barns and other buildings of the peasants while beyond this

concentration of dwellings lay the fields, the meadow, woodland and the fen. Corn crops were grown in rotation with one field fallow each year and providing common pasture for sheep and cattle. Grazing would also be found on the meadows after the gathering in of the hay crop and on those parts of the fenland that were not too inundated or boggy. There was also land on which pigs could roam and feed in the underwood to the west of Bourne while more fields surrounded the dwellings of peasants at Cawthorpe and Dyke.

The general agricultural pattern of a large part of medieval England and descriptions of the manorial system are well documented. But modern research is showing how difficult it is to generalize in this complex field of our social history and while certain very broad principles underlay mediaeval agriculture in every region, there were a host of local deviations from any standard system. Ancient custom, geographical conditions, and various other factors, combined to give each locality its distinctive farming arrangements that were in some degree different from those in other parts of the country. What then were the main features of mediaeval farming in Bourne, so far as we can ascertain from the evidence at our disposal, and the work already done by historians?

In the earlier part of the Middle Ages, villages lying along the western edge of the fen had three or four field systems of farming, i e there were three or four large arable fields divided into strips, each villager holding his share of the latter with a commonly accepted form of crop rotation. If we are to accept the 18th century pattern of Bourne before enclosure as indicative of the

mediaeval layout, we see that it indicates the four field system in operation. To the north-west of the town, between Bourne Wood and the road running north to Lincoln, now the A15, lay North Field. On the other side of that road lay East Field, while South Field extended across the southern part of the parish and to the west, on both sides of the road running out to Stamford and Grantham, lay West Field.

It is interesting to see that both Cawthorpe and Dyke, which lay within the parish of Bourne, had their own open fields, at least three to each community with names rather more picturesque than the plain geographic terms used for the Bourne fields. Cawthorpe had its Cawthorpe West Field but it also had Hasleland Field lying to the north and Quinto Field to the north and east. To the north of Dyke lay Moor Field, then Wath Field to the east and Nutto Field to the south.

An assumption by historians that the expanse of fen to the east of the Car Dyke was completely flooded and unreclaimed before the drainage work of the 17th century has been strongly challenged in recent years and it is now clear that reclamation was going on in the early Middle Ages. The men of South Lincolnshire were skilled at drainage in the 12th and 13th centuries, able to control rivers by means of sluices and to win land in the fen and on the coast by the construction of suitable banks. Despite many seriously wet years and severe flooding by the sea in the late 13th century, the combined work done by the fenland peasantry resulted in the settlement of large areas of the silt land of Holland and the area round the Wash. On the western fen edge, the reclamation was also being steadily carried on and in Bourne, it is clear that by 1300, cultivated land had stretched out to the east side of the Car Dyke and at about this time, the East Field already extended beyond the waterway and there were also in the same area, stretches of meadow as well as cultivated strips.

Some evidence that fenland was being enclosed for agriculture is found in a charter of 1270 in which Baldwin, son of Hugh Wake, granted

the Almoner of Spalding Priory ten acres of land in Bourne in Neulond,

abutting south on the road to Oldhee, north on the way to Gubaldispark.

The latter, known in more recent times as Gobold's Park, lay well into the fenland, some distance to the east of Meadow Drove. So the ten acres

in question must have been not far from there, and well to the east of the

Car Dyke. In fact, being in Neulond, this land was close to the farm still

known as Newlands Farm, near the Bourne end of Meadow Drove.

Newlands Farm, to the south of Bourne.

From quite an early date in the mediaeval period, governmental activity also encouraged the prevention of flooding in the area which later became

known as the Black Sluice district, stretching eastward from the Car Dyke to Boston. In

1207, the inhabitants of this region were freed from all

duties relating to forest customs and preservation of wild animals, with leave to make banks and ditches, and to enclose the lands and

marshes, also to build houses and to exercise tillage. In 1260, Henry III showed

concern about the state of Holland Fen, and commanded the shire reeve [a local official or bailiff] to

absolve all landowners from repairing banks, ditches, or bridges. The flooding of Holland Fen by the water which flowed down from the higher ground to the west of the Car Dyke was a frequently recurring problem in the 13th and 14th centuries and the inhabitants of Bourne were more than once reminded of their duty to see that the Bourne Eau was an effective part of the drainage system. In 1293, for instance, at an inquisition at Gosberton, the jury found that

Brunne Ee, Tolham, and Blake Kyrk ought to be repaired, raised, and scoured by the town of Brunne to Goderamscote (Guthram Gowt) on the north side; and on the south to Merehime, beyond which the town of Pyncebek ought to repair it unto Surflete; and the town of Surflete from thence to the

sea.

Only fourteen years later, the king's justices sat at Boston to enquire into the drainage of the fens and reported that the whole marsh of Holland and Kesteven was overflowed and drowned. Among other things liable to repair was

Burne Aide Ee, running from Bourne through Surfleet to the sea, the first stretch from Bourne to Guthram Gowt belonging to the town and Abbot of Bourne jointly. Various later commissions made similar reports and one which was held at Thetford in the 14th century was quite specific in its recommendations, saying that

the banks of the river of Brunne ought to be enlarged from Leve Brigg in Brunne unto Tollum, and be made 2 feet higher and 12 feet thick, and that the town of Brunne ought to cleanse the Narwhee from Brunne to Godram's

Cote.

Drainage considerations were therefore a major issue in the history of our agriculture and the use of land in mediaeval Bourne. In the open fields, as well as in the meadow such as Gobold's Park, the strips or selions were arranged in furlongs, as was the general custom in the Midlands. On the arable strips, there would no doubt be a three-year rotation of crops, two years of corn alternating with a fallow year while the meadow could be used for a hay crop in summer with grazing later in the year. But we must beware of dividing arable, meadow, and common fen land into completely distinct categories, each entirely separate from the other. In fact, the open fields sometimes contained land that was not arable, and conversely, there

were sometimes arable areas in the enclosed meadows while the common fen often contained private enclosure. The fenland selions were not exclusively arable but could be meadow, pasture, hempland, flaxland, turbary [for turf or peat] or reed beds. Unlike those elsewhere, they were not separated from each other by balks of land but were often surrounded by dykes or cuts of water. In short, so far as the land on the fen edge is concerned, the picture is a confused one, with arable, pasture, and meadow very mixed.

|

|

|

A potato crop in the South Fen, Bourne (above), and a crop in the same

area being spray irrigated with water drawn from nearby drainage dykes

during a dry spell is pictured below.

|

|

|

It is clear that in this mingling of different types of farmland, the proportion of arable land to other kinds was very great. This

could vary considerably, as needs required, and although the available figures are not conclusive, they do have significance. In a survey made at Bourne in 1265, when Baldwin Wake was Lord of the Manor, there were 180 acres of arable (90% of the total), 20 acres of meadow (10%), and no pasture land recorded. In a much more detailed survey of 1282, there were 204 acres of arable (77% of the whole), 47 acres of meadow (17.7%), and 14 acres of pasture (5.3%). These surveys did not record the great common fens and marshes which would also contain a considerable amount of pasture land but the predominance of arable land which they show reflects the great demand for grain in the 13th century, a time when the population of the fenland was rapidly growing.

There is no doubt that many of the new landowners who appeared in the 16th and 17th centuries were men who had both the money

and the inclination to improve agricultural production. There was a general concern about improving, and a desire to use every possible method and every available bit of ground. On the arable fen land, the Dutch plough was used, with a broad share that was sharp enough to cut through matted weeds or sedge. On the hilly land, it was the plain plough, without wheel or foot. Either horses or oxen might draw the plough and it was still debated which were better. A variety of other tools and implements was at hand such as the harrow, the clodding beetle [resembling a carpenter's mallet but with a longer handle], the roller, fork, scythe, sickle, rake, flail, sled, dung cart and corn cart or wagon, sometimes with iron bound wheels. Many of these tools were made by hand, near the fire on winter evenings. Seed was carefully selected, sometimes coming from far away. Wheat was reaped with a sickle or a hook, barley and oats were usually mown with a scythe while peas and beans were reaped or sometimes mown. In Lincolnshire, barley was mostly used to produce beer but could also be turned into bread or into a boiled mash for feeding to animals.

Great stress was now being laid on the importance of manure and for most farmers,

sheep dung was the best, hence the folding of sheep on the common fields, but even such commodities as malt dust, hair from animals, decaying fish or offal were used as fertilisers. Sheep and cattle were also found on the pasture land that existed both on the higher ground and in the fens. In the latter, which were often overflowed in winter, there was a plentiful crop of grass in summer and abundant grazing for all who had common rights. Bourne South Fen or Cow Pasture was no doubt such an area and probably most people in the town would have one or more animals which they could put there although there were strict regulations against allowing diseased beasts on the common land.

While large farmers might have several dozen cattle, the cottagers, and probably also the tradesmen of the town, would have a cow or a few sheep or even a horse which they could put on to the common pasture. The cow was the most useful animal of all as it could supply milk, cheese, and butter, thus providing reasonable nourishment even if its owner could not afford meat. In the Lincolnshire fens, the cattle were

pied but more white than anything, with small, crooked horns, tall bodies, and large but lean thighs. However, the trade in cattle was already nationwide and so a variety of breeds might be found in any particular district. The fenland sheep was a Lustre Longwool, like those found in the Midlands. It was the largest of existing types, with long legs and a heavy fleece of long, coarse wool. Horse breeding was quite common in pastoral areas like the fens and these horses were often sent to the coal pits of Nottinghamshire, to the Derbyshire lead mines or to Yorkshire breeders who mated fenland breeds with their local ones. But not many of the ordinary labourers kept horses and those who did used them mainly for carrying goods in panniers or nets, carting corn or wood, and conveying their wives to market. When a plough animal was needed, most labourers borrowed one for a day or two. Many peasants kept a pig, but it was only the larger farmers who produced pigs for market. Poultry was also quite common, geese especially being found in the fens, and their feathers and grease were sold as well as their meat.

An oil seed crop at Careby, near Bourne.

One aspect of Tudor and Stuart farming which has received widespread attention from historians was the enclosure of arable land and its conversion to pasture and also the enclosure of the common land. A growing population meant more livestock, which in any case was a vital factor in farming because of the manure produced. Rising agricultural prices in the 16th century also made large farmers anxious to produce on a greater scale and so the demand for grassland increased. In many areas of the country, enclosure caused definite social upheaval and where it was followed by the conversion of arable to pasture land, unemployment followed as fewer labourers were now required. Engrossing, or the amalgamation of two or more farms into one, was also going on in this period and this contributed to depopulation. But in Lincolnshire, and especially in the fenland, these processes do not seem to have caused the controversy and resentment that appeared in some other places although a certain amount of enclosure was evident in Bourne during this period.

In the enclosure award of the 18th century, there are quite frequent references to "ancient enclosures" lying adjacent to unenclosed land. These appear in most, if not all, of the open fields, e g in North Fen there were the North Fen Pastures, in Newlands there were the Frier Bar Pastures and adjoining the north bank of the Eau was an enclosure known as the Tallow. Even in South Fen, there were "certain ancient enclosures" surrounding a decoy that belonged to the Earl of Exeter. We cannot be sure precisely when these pre-18th century enclosures were made. There had been some fenland enclosure in the early Middle Ages and in the 16th and 17th centuries the process may well have been resumed with as little upset as in those earlier times.

The farmers who were considered to be lower in status than the gentry were classified by various names. The word farmer was rarely used before the mid-17th century. In some parts of the country, yeomen were common, in other places husbandmen, although this term was normally applied to a person who rented his land, and yeoman to one who owned it, although variations from this can be found. In the parish registers of Bourne, both terms occur occasionally but far more often we find labourers. It seems that this designation covered a fairly wide range of farm worker. At the lower end would doubtless be those who had little or no land of their own and who worked for a wage for an employer but in Lincolnshire there were also labourers who were no poorer than husbandmen elsewhere and who often had land of their own.

Most labourers had some livestock but hardly in sufficient quantities to be classed as flocks or herds. A man might have one or two cows, providing milk, cheese and butter for his own family and his wife would take any surplus to be sold at the market. In Eastern England, labourers' flocks of sheep, if they could be so called, ranged from about three to nine animals in each. Many would keep a pig and would have flitches of bacon hanging inside their cottages. Horses were not very common among this section of the community in which many workers could not afford arable land so had no ploughing to consider and bought their grain in the local market each week or from travelling salesmen. The majority of labourers obtained their livelihood by working on a farm for a wage. Their work was perhaps monotonous but there was opportunity for a wide variety of tasks such as ploughmen, shepherds, haywards [maintaining fences], thatchers, carpenters and gardeners. Some men would tend to specialise in particular crafts while women and children were employed for jobs needing little skill such as stone gathering, weeding, cutting rushes or picking apples.

Bourne was in the centre of an agricultural region and therefore shared in the increased prosperity that came with the extensive improvements in farming which began in the later years of the 18th century. Foremost among these changes was the enclosure of the land for private ownership, which in fenland areas, including Bourne, was also coupled with drainage. These developments brought rich returns to the gentry and larger landowners and we have a revealing insight into farming life in the area at the close of the century from Arthur Young who made a detailed study and published his findings in his

General View of the Agriculture of the County of Lincoln in 1799.

He listed the places where enclosure had been done and added: "The rents have been doubled in consequence." With more capital and the advantages of new techniques that were rapidly spreading, the farmer could increase productivity as never before. Even the poorer classes must have shared to some extent in the rising prosperity and though historians have often been at pains to stress the hardship caused to the poor by the enclosure of common land, it is clear that in Bourne, at any rate, very real consideration was given to the humbler folk at the time of the enclosure awards.

Enclosure of the open fields and of parts of the fenland had been started in earlier times and the Bourne enclosure documents of the 18th century contain numerous references to "ancient inclosures". But in the fifty years after 1760, enclosure by Act of Parliament became common over large areas of southern England and the Midlands and during this time, Bourne was also involved in the process. The Bourne Enclosure Act was passed in 1766 and four years later, the award of the various lands to their new owners was made. This Act concerned two main areas of land in Bourne, firstly, some 2,450 acres of open fields and meadow, described as being "intermixed and dispersed in small parcels, and therefore were not then capable of any considerable improvement", and secondly, about 4,400 acres, "certain large common fens, called the North Fen, the South Fen and Dyke Fen, which were frequently overflowed with water and were but of little use to those who had right of common thereon". The procedure by which the land was allotted for enclosure, and arrangements for drainage made, was similar to that employed in most places. The Act passed by Parliament in 1766 was no doubt a result of the initiative taken by principal landowners in the parish who were dissatisfied with the inefficiency of the existing farming arrangements and anxious to secure improvements.

|

|

|

The corn harvest

underway at Careby, near Bourne (above). The photograph below shows wheat being loaded

near

Dyke ready for farm storage. |

|

|

|

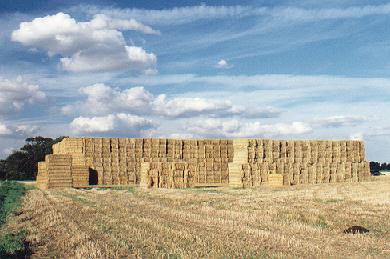

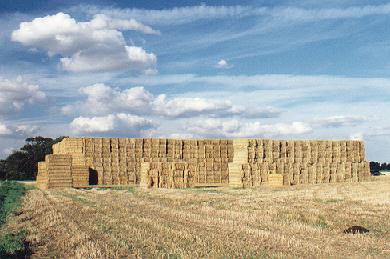

Baled straw after

the harvest is pictured below in both round or big bales,

photographed at Hanthorpe (left) and the

traditional rectangular bales, photographed near Wilsthorpe

(right). |

|

|

|

In 18th century Lincolnshire, the keeping of cattle was widespread and not confined solely to the farmers and yeomen. Even tradesmen and cottagers in Bourne obtained their share of land during the enclosures and the great majority of these people would have one or more cows. In 1689, in his will, John Mottram of Cawthorpe defined the poor as those who possessed only one. In some parts of the county, oxen were still being used for ploughing or carting although this practice was gradually dying out. Disease was a serious menace to cattle, especially in the days before enclosures, and there were some disastrous years such as 1747 when cattle plague swept through the whole county. Nevertheless, by the end

of the century, the quality of beasts bred in Lincolnshire began to improve.

The native Lincolnshire cattle were carefully crossbred with animals from Holland, Durham, and Yorkshire to produce the red shorthorn breed.

Arthur Young commented that the Lincoln shorthorns seemed to be more profitable than the celebrated longhorns from Leicestershire but it was not until the 19th century that the Lincoln Red became the standard breed. Lincolnshire sheep were also being improved from the 17th century onwards and some of them were now being used in Leicestershire where the famous breeder, Robert Bakewell, was evolving his New Leicesters. Young discovered that there were many breeding flocks around Grimsthorpe, generally a cross of the New Leicester, but "on the level beyond Bourne, they are more of the Lincoln, the greatest part of them having cole [kale] on their farms, by which they can make that breed fat".

Young was greatly impressed by the grasslands he saw as "the glory of Lincolnshire" and mentioned in particular a belt of rich grazing land two or three miles broad, running from Sempringham down to Deeping, on which both sheep and cattle were grazed, although some of it was in tillage. In fact, much of South Lincolnshire was grazing land until well into the 19th century.

Horses were by now widely used for various kinds of farm work, even supplying the motive power for some of the machinery that was beginning to appear and doubtless many of the townsfolk also possessed a horse for transport. But amongst the humbler cottagers, horses would not be so commonly found as were cows, sheep, and pigs. In Arthur Young's summary of the state of the Lincolnshire poorer classes, it is cows and pigs which are mentioned: "It is impossible to speak too highly in praise of the cottage system where land, gardens, cows, and pigs are so general in the hands of the poor", he wrote.

Until the growing of potatoes became general, it would be the cow, not the pig, which was the mainstay of the poor. As in earlier days, large numbers of geese were still kept and plucked four or five times a year. Decoys for taking wildfowl were also quite common in the fens and in the Bourne area, the Earl of Exeter's decoy in the South Fen, adjoining the Bourne Eau, was particularly renowned.

The 18th century brought a considerable variety of crops to Lincolnshire but the amount of arable land was much smaller than today. Among the corn crops, barley was prominent and in times of scarcity provided bread for the poor. Arthur Young found barley growing in Deeping Fen, estimated at 12 quarters an acre, while around Grimsthorpe, barley, wheat, oats and beans were produced. Beans were very common but they

were not well managed because drilling was not understood and hoeing usually ignored. Cole was grown on many farms near Bourne, being a plant on which sheep could be fed. Rape was also to be found and Young again mentions Deeping Fen as an area for its growth for the provision of sheep fodder while its seeds were used to produce oil.

A crop of flax in blossom on the outskirts of

Wilsthorpe, near Bourne, with

poppies growing at the field's edge where they have escaped the

chemical sprays.

Flax and hemp were still being quite widely cultivated in Lincolnshire and the potato was increasing in importance. Young reported many potato fields round Spalding and noticed that near Folkingham, the cottagers especially had taken to potato growing during the closing years of the century. Turnips, which were growing in the country in the 17th century, had spread very quickly although they had not been widely grown before 1770, and, like beans, were badly drilled and not often hoed.

The development of farm implements was another feature of agricultural

improvement in the eighteenth century, and Young tells us that some of the new machinery that he discovered in other parts of the county was being adopted by the richer and more enterprising farmers in this district. In the fens, a plough with a wheel coulter was being used rather than a sword one, as this was better for ploughing in stubble and twitch grass and produced good, straight furrows with two horses. Around Osbournby, he

discovered they were using the Norfolk wheel plough that did well on lighter soils.

Other newer implements he found in use included drilling machines, expanding horse hoes, chaff cutters and threshing machines worked by two or four horses, although most of the manual work involved was done by women, and reaping machines that were still in the experimental stage. New inventions were clearly transforming agriculture at this period and it is clear that Lincolnshire was beginning to experience the first stages of the agrarian revolution.

But there was still a great deal of woodland around Bourne. The Earl of Exeter, as Lord of the Manor of Bourne, had extensive woods in this area

from which the underwood and timber brought him in about 20s. per acre per annum and a great deal of this timber was used in fencing enclosures. The improvements to the land had brought a general rise in rents during the century and by the end of this period, land within a five-mile radius of Grimsthorpe was being let at 15s. an acre, although some grazing land was worth 30s. On the other hand, where open fields still existed, it was only six or seven shillings an acre.

Young found that the wages of labourers were comparatively high and considered them probably higher in Lincolnshire than in any other county. At Grimsthorpe, he discovered that a farm worker was getting 9s. a week in winter, rising to 12s. in spring and summer and reaching a peak of 18s. a week in harvest. For reaping, he received 10s. 6d. per acre. Women were getting much smaller wages and at Folkingham they received 5s. a week in summer and for spinning flax and hemp from Holland Fen, they were earning 6d. a day. Whether these fairly high wages had brought any great improvement in the labourers' standard of living is by no means certain because prices, too, had generally risen. In 1759, butter had been 3d. a pound and forty years later, it was 10d. In 1786, beef was 2d. a pound but in just over ten years, the price had doubled. The war against France, which began in 1793, was a major cause of rising prices and it has been estimated that in 1798, despite his increased wage, it would take a labourer just as long to save up for a quarter of wheat as it did 20 years earlier.

|

|

|

The sugar beet harvest underway on a dull winter's

day in the fen between Bourne and Dyke.

|

|

|

Bourne's prosperity in the 19th century was still closely linked with that of agriculture and a directory of 1857 gives a list of farmers that is considerably longer than that of any other occupation in the town. Farming experienced numerous vicissitudes and fluctuations during the century and it was far from being a period of steady progress. In the war years at the beginning of the century, there was prosperity with high prices for corn and rents reaching a good level. Labourers, however, were not so well off, for though they would usually be able to find employment, their average wage of 12s. a week (in 1813) made living expensive. With the coming of peace in 1815, agriculture experienced

a general setback. Wheat, which had averaged 88s. a quarter between 1807 and 1816, fell to 38s. by 1822, and rents dropped accordingly. But although the arable farmer suffered considerable hardship in these years, it was not a picture of universal gloom because the total wheat production of the country continued to rise and the livestock farmer was much less affected than the producer of grain. As for the farm labourer, his wage had remained about the same and if he could find employment, he might be better off because of a subsequent fall in food and clothing prices. But conditions generally in the 1820s and 1830s were poor compared with those of a later period.

From the middle of the century, there was a greater degree of prosperity and this period is traditionally known as the Golden Age of English agriculture. Although, after 1846, British corn was no longer protected against foreign competition, the dismal forebodings of Protectionists that farming would now be ruined proved unfounded. During these mid-Victorian years there was a sustained boom in industry which had a beneficial effect on farming because a more prosperous urban working class could now afford to buy more of the farmer's products, including meat as well as flour. It is perhaps no coincidence that we should find in these years evidence of much new building in Bourne.

In the late 1870s, British farming suffered a series of blows, some of a temporary, others of a permanent nature. Their effect was to initiate

what historians have often called "the great depression in agriculture" which left a permanent mark on the industry. A

succession of bad harvests, serious outbreaks of foot and mouth disease amongst cattle and liver rot in sheep, together with a general recession in trade, were bad enough in themselves, but such afflictions could be expected to pass in time. Combined with them, however, was the entry on a massive scale into Britain of grain from the new prairies of North America and this was not to be a mere temporary factor. From now on, Britain was to find it cheaper to draw her wheat supply from other lands and consequently, there was a sharp fall in British corn prices from which arable farming never really recovered until the Great War of 1914-18. Prices of grain in Lincolnshire fluctuated a good deal and varied from one place to another but the general downward trend in the last quarter of the century was unmistakable. Wool also experienced a fall in price similar to corn with consequent hardship to the sheep farmer. Home produced meat also began to encounter competition when refrigeration in ships made it possible to import frozen beef and mutton from overseas but meat prices did not drop quite so dramatically as those of corn.

The main crops grown in Lincolnshire in the 18th century continued but with certain variations into the 19th century. Barley was still grown extensively and wheat and oats were not far behind in importance. Turnips, peas, and beans were also widely cultivated while the potato now came into its own as one of the principal crops. In the later years of the century, in the potato growing lands of South Lincolnshire, the railways were giving a free delivery up to a distance of three miles, and rents were reaching the comparatively high figure of £3 an acre. As for livestock, there was a slow improvement in cattle rearing in South Lincolnshire. In the second decade of the century, shorthorns were

introduced, and later on the celebrated Lincoln Red appeared. By the end of the century, this animal was renowned for its hardiness and good milking qualities. The Lincoln long wool sheep disappeared by the 1820s to be replaced by the Lincoln-Leicester crossbreed, producing both good quality wool and mutton. Lincoln sheep were exported for breeding purposes to several countries overseas. In 1898, a Lincoln ram fetched four figures in a public auction sale for the first time when it was bought by an agent acting on behalf of a South American buyer, despite the efforts of Messrs S E Dean and Sons, of Dowsby Hall, to keep the animal in England, by bidding up to 950 guineas.

Horses were still widely used for agricultural purposes, as well as for transport, at least over short distances after the railway age began. In 1903, the county contained over 56,000 horses used for farm work, including mares for breeding, which was only 12,000 less than the total of cows and heifers in milk or in calf. Pigs and poultry were still widely reared, almost every labourer having one or two pigs, with local Pig Clubs to provide insurance against loss or disease. The mass breeding of geese in South Lincolnshire, which had been a feature of earlier generations, was by now dying out, as drainage of the land gave less scope for this industry.

The increasing use of machinery in Britain and the advent of steam power brought significant changes to farming during these years. The new implements that had begun to appear in the late 18th century only spread widely in South Lincolnshire after about 1820.

Manufacturers of agricultural machinery

staged demonstrations around the county in a bid to tempt buyers and the Stamford

Mercury reported on Friday 12th August 1864:

During

the past week, one of Samuelson's and Ransome's combined patent reapers,

supplied through Mr H Osborn of Bourne, has been in operation upon the

farm of Mr Wilson Barnes of Toft. Several practical farmers who witnessed

the trial expressed entire satisfaction at the manner in which the work

was done. Other reapers previously introduced into this

neighbourhood having failed, it was a matter of some surprise that one had

been brought apparently so near perfection. It is worked with two horses

and a man to drive them and will cut about ten acres a day; other men, of

course, being required to tie up the corn. The cutting is unexceptionable

and the laying of the corn when dry is exceedingly well done. It is

believed that the time is not far distant when a reaper, simple in

construction and moderate in price, will come into much more general use.

A second report on the new machines

appeared in the newspaper on Friday 2nd September 1864:

Another

trial of Samuelson's and Ransome's combined patent reapers took place last

week upon the farm of Mr Henry Bott, of Bourne, when a large field of

beans was cut in a very satisfactory manner at the rate of about one acre

per hour.

By this time, many new kinds of plough had been designed, while machines like the seed drill and the threshing machine were rapidly developing, the latter now driven by steam-power which at first appeared on farms in the shape of a portable engine but this largely gave way to the traction engine. By 1900, some of the big Lincolnshire farmers had their own steam traction engines that were used for threshing, sawing, grinding, and hauling of bulk goods like corn or coal. They were also being employed for ploughing, although the steam plough had its difficulties, and it lingered on in only a few places after the arrival of internal combustion engines. Steam power was also used for fen drainage and there was even a steam flour mill in Bourne, situated on the corner of Goggles Causeway and South Road and mentioned in 1871 as being "lately erected" by a miller, Thomas Heaton. Another important invention, coming into use in the second half of the century, was the reaper that eventually incorporated the self-binder. This revolutionised the corn harvest and by 1900, with sometimes as many as four binders at work in one field, the demand for extra seasonal labour had been greatly reduced and although the old methods still persisted in many places, the general trend was clear.

Until then, additional labour was required

each year to bring in the harvest and the Stamford Mercury reported

on 24th August 1888 that: "The immigration of Irish labourers in the

district has set in. The recent fine weather has had a beneficial effect

on the crops generally. By the end of the present week, the cutting of

oats will be in full swing."

New manures had begun to improve agricultural output although their adoption was rather slow in this locality. But, in general, the chemical fertiliser industry developed quickly from about 1840 onwards. Chilean nitrate began to be imported in considerable quantities as well as

guano [the dried excrement of fish-eating sea birds] that soon became a well-known fertiliser in Britain.

By the 20th century, Bourne had become the centre of agricultural activity

in this part of South Lincolnshire while farmers and farming played a

significant part in the life of the community. By now, a large part of the

fenland to the east and south of the town was arable, producing mainly

potatoes, sugar beet, wheat and barley although oil seed rape and flax

were emerging as popular alternative crops by the end of the century. The

occasional pasture that can still be found is a reminder of the days when

the fens were noted for their grassland and there is more pasture on the

higher land to the west although here again there has been extension of

the arable farming of past years.

Farming has become a highly mechanised industry with bigger holdings and larger fields that are maintained, ploughed, seeded and sown by a single tractor instead of the labour intensive activities of previous years. The farms that once employed dozens now have two or three on the payroll but they are better educated and need to be computer literate to operate some of the more sophisticated machinery, their pay is higher and they have pension entitlements. A good farm worker, as opposed to the old term of labourer, now has the choice of where he will work because they are becoming increasingly hard to find.

The growing of crops too, has been overtaken by progress, and they are often sold before they are planted, the soil and conditions becoming part of the overall strategy for the growing year planned by the farmer in conjunction with the buyer. Agriculture has become a streamlined industry,

often run by college graduates, where crop failure is rare and production increases year on year and the farmer can forecast his profit when the seed is sown.

The production of a wide variety of vegetables such as peas and beans has also produced another industry for the town where several factories have been established for freezing and packing and as the century closed, yet another industry began with the opening of a plant specialising in herbs that are sold on the international markets. Bourne's reputation, and indeed prosperity, in the field of agriculture, based on the experience of 2,000 years, has now spread world wide.

|

PHOTO ALBUM |

|

|

The farming landscape on the uphills near

Obthorpe, to the south west of Bourne, pictured (above) showing a mix

of uses from intensive wheat cultivation to oil seed on the left and

pasture land on the right, and a wheat crop in the fen between Bourne and

Dyke village (below). |

|

|

|

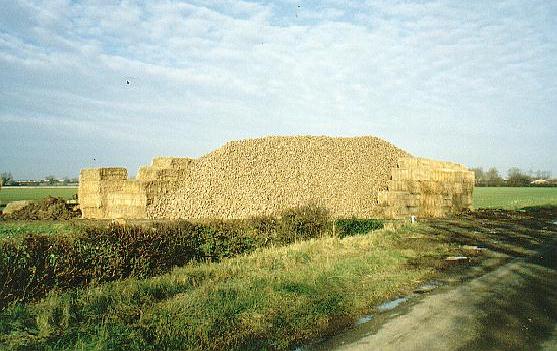

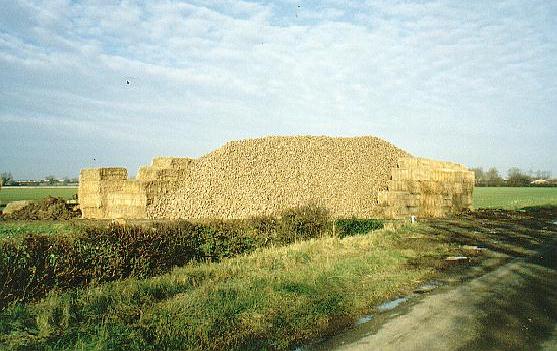

|

A crop of onions on the outskirts of

Wilsthorpe, near Bourne, lifted and

left out to dry in the sun (above) and sugar beet just harvested from

surrounding fields in a surface storage site created by bales of straw

alongside Meadow Drove near Dyke, waiting to be moved by lorry to the

processing factory.

|

|

|

|

Intensive farming means crop spraying to

control weeds and insects such as here in this field of wheat to the

north of Bourne although it is widely believed that our flora and

fauna also suffer with the result that we have fewer wild flowers,

birds and animals in the countryside. |

|

|

The land lies idle between harvest and ploughing, a sea of wayward

straw and stubble such as here between the north of Bourne with Dyke

village and Morton church on the skyline, but this is a short period

and soon the earth will be turned again in readiness for another

growing season in the unending cycle to provide the nationís food. |

|

|

Efficient drainage relies on a well maintained

network of ditches and dykes to carry the water away from acres of

farmland vulnerable to flooding and here a contractor working on a

bleak November day uses a JCB to clear silt and vegetation from a

channel alongside a country road near Hanthorpe, north of Bourne, an

operation known hereabouts as roding. |

|

|

Cattle grazing in field alongside the A15 road between Bourne and

Morton village, a less familiar sight since the foot and mouth

epidemic of 2001 which caused a crisis in agriculture and prompted many farmers

to concentrate on arable farming

rather than livestock. |

|

FROM THE ARCHIVES |

|

We are sorry to find that the farmers in the

neighbourhood of Bourne are compelled, from the low prices of

farming produce, to reduce wages to 10s. a week. - news report

from the Stamford Mercury, Friday 2nd December 1842. |

NOTE: This article includes edited

extracts from General View of the Agriculture

of the County of Lincoln by Arthur Young (1799) and

A History of Bourne by J D Birkbeck (1970).

REVISED APRIL 2015

Go to:

Main Index Villages

Index

|