|

William

Cecil

- the first Lord

Burghley

1520-1598 |

|

The Burghley Arms in the town centre at Bourne is traditionally regarded as the birthplace of the illustrious English statesman William Cecil, trusted chief adviser to Queen Elizabeth I and the first Lord Burghley.

Burghley, also spelled Burghleigh, was known as Sir William Cecil from 1551 to 1571. He was a pillar of state through three reigns and for forty years was the main architect of the successful policies of the Elizabethan era, earning a reputation as a master of renaissance statecraft whose talents as a diplomat, politician and administrator won him high office and a peerage. He was created the 1st Baron Burghley in 1571 and the following year he became a Knight of the Garter and Lord High Treasurer, an office he held until his death.

The Burghley Arms was formerly a private residence until the 18th century when it became a coaching inn, first known as the Bull and Swan and then in the 19th century, the Bull, but the name was changed to the Burghley Arms during the mid-20th century to associate it with the town's famous son and in recent years a plaque was installed on the front bearing the inscription:

|

William

Cecil,

Lord Burleigh K G,

Lord High

Treasurer

in the reign of

Queen Elizabeth I,

born here

13th September 1520

|

|

Cecil's family had acquired wealth, office and the status of gentry through their service to the Tudors and the marriage of his father Richard Cecil, of Burghley in Northamptonshire, to a local heiress. He married Jane Heckington, daughter of William Heckington, owner of the Manor of Bourne, which eventually passed into the Cecil family and remained in the hands of successive earls of Exeter until modern times.

In his childhood, William served as a page at court where his father was a Groom of the Wardrobe. He was educated at Stamford and Grantham and in 1535, he entered St John's College, Cambridge, where he studied classics under the humanist Sir John Cheke and came under Protestant influence. He fell in love at the age of 20 with Cheke's sister Mary, and they were married in 1541, a few months after he had entered Gray's Inn, but she died in 1543, leaving him a son, Thomas.

In 1542, for defending royal policy, Cecil was rewarded by Henry VIII with a place in the Court of Common Pleas and a year later he first entered Parliament. Through his second marriage to the learned and pious Mildred Cooke in 1545, he joined an influential Protestant circle at court and when Edward VI succeeded to the throne, Cecil joined the household of the protector, the Duke of Somerset, and in 1548 became his secretary. On Somerset's fall from power, Cecil shared in his disgrace and was imprisoned in the Tower of London for two months in 1549 but his pre-eminent abilities soon regained him royal favour and in 1550 he became one of two secretaries to the king who granted him the honour of a knighthood the following year.

He had little scope under Edward VI but nevertheless established himself as an able bureaucrat and although offered employment on Mary's accession, preferred to withdraw from the Catholic court. But on Elizabeth's accession in 1558, Cecil became her principal secretary and his illustrious career blossomed. They sought to improve the economic footing of England, among other measures adopting a new coinage. To heal the religious division of the country, they prepared a compromise settlement that resulted in the establishment of the Anglican Church in 1559. Cecil also ended a costly war with France, strengthened the army and navy, and organised an efficient secret service.

Cecil's close scrutiny of the activities of Elizabeth's cousin, Mary Stuart of Scotland, led to her trial for treason and her execution in 1587. His insight into the intentions of Spain and his preparations for resistance, especially by sea, culminated in the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588. He exploited victory with propaganda and his fame as principal councillor of Elizabeth spread throughout Europe.

As Chancellor of the University of Cambridge from 1559, Cecil influenced discipline rather than the curriculum but he made his household a resort of scholars and an educational centre for the Queen's wards and the young aristocracy. His intellectual interests, like his italic handwriting that had been developed for popular use in the early part of the century by the Vatican chancery scribe Ludovico degli Arrighi, were formed in the advanced humanist circle of Sir John Cheke while his eclecticism was revealed in his personal vision of three grand houses, Burghley House at Stamford, Cecil House in the Strand and Theobalds in Hertfordshire and his spending was lavish in the building and beautifying of these mansions. He supervised their planning and decoration, furnishings, collections of pictures, coins and "things of workmanship", and their gardens supervised by the botanist John Gerard, won universal admiration. In fact, Cecil made a creative contribution to the Elizabethan architectural achievement.

There is also some evidence that he remembered his birthplace by bestowing a new Town Hall on Bourne. William Camden, the scholar, antiquary and historian (1551-1623), who undertook a survey of the British Isles and subsequently published his findings in Britannia, published in 1586, wrote: "In the centre of the market place is an ancient Town Hall, said to have been built by the Wake family. The Cecil arms are carved in basso-relievo over the centre of the east front and this Town Hall was probably rebuilt by the Lord Treasurer Burghleigh." It stood on a site near the junction of South Street and West Street and underneath the building would have been a shambles and stalls which formed part of the weekly market while the Quarter Sessions were held in the Town Hall itself which also became the meeting place of the court of the Manor of Bourne of which the Lord was then the Marquess of Exeter. By the beginning of the 19th century, this building was in a dilapidated condition and so it was decided to build a new Town Hall, which was erected in 1821 and still serves the town today.

After the failure of the Armada, Cecil survived to preside over the politics of a new generation. He coached his son Robert, born in 1563, for the secretaryship which he obtained for him in 1596 but despite ill health, Cecil remained active, performing his official duties, writing memorandums and dealing with suits but he devised no new policies to check declining prosperity. Instead, he intensified a programme of retrenchment and pressed the Commons for grants. In foreign affairs he supported campaigns waged against Spain in France and the Netherlands and naval expeditions by Drake and Essex but finally urged peace with Spain, fearing a Franco-Spanish settlement and the strain of prolonged war.

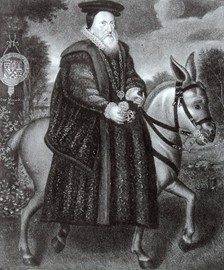

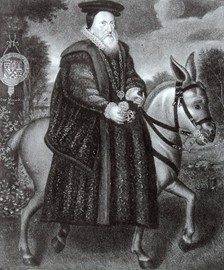

He died in London on 4th August 1598 at the age of 77 before the negotiations were concluded and was buried at St Martin's Church, Stamford, which contains the Burghley Chapel, richly decked with monuments of the

Cecil family, including his own effigy, lying on his marble and alabaster tomb, richly carved and painted and filling the arch dividing the chapel from the chancel. William Cecil may have seen it for it was designed before his death. It shows him in his armour wearing the gorgeous scarlet mantle of the Garter, a noble figure nobly arrayed, his head on

a pillow of gold brocade, his wand of office in his right hand and a lion at his feet. His father and mother, Richard and Jane Cecil, kneel at a prayer desk on the wall close by and have three children with

them.

|

|

|

|

The tomb of William Cecil in St Martin's

Church, Stamford, made from marble and alabaster, richly carved and

painted and depicting him in armour and wearing a scarlet mantle of

the Order of the Garter as shown in this famous portrait. |

|

THE SHAKESPEARE

CONNECTION

Polonious, a character in William Shakespeare's

Hamlet, is sometimes referred to as a parody of Lord Burghley, a

theory that dates from Victorian times but is also widely disputed

as being unlikely and uncharacteristic of the Bard yet the

references remain.

|

|

The father died in 1552, little dreaming of the

eminence his son was to attain. There is no memorial to William Cecil in Bourne

apart from the tiny plaque on the front of the Burghley Arms public house.

Several other locations around the town bear the family names including the

Burghley Centre, Burghley Street and Burghley Court, together with Exeter

Street, Close, Court, Gardens and Row, but he is better remembered in Stamford

than in Bourne. Burghley House is the largest and grandest house of the first

Elizabethan age and was built between 1565 and 1587 and the house remains a

family home for his descendants. It is set in a picturesque deer park designed

by Capability Brown and is open to the public from April to October when

visitors are invited to see this most spectacular of houses and the treasures

within it, a fitting tribute to one of England's foremost statesmen and the

trusted and able adviser to Queen Elizabeth I.

|

THOU GOOD AND FAITHFUL

SERVANT

Deceit, perfidy, treachery and worse have been the mark of many politicians through the ages and there can be no one who assumes power that does not envy the unswerving and devoted allegiance that was paid to Queen Elizabeth I by her right hand man, William Cecil. He was the first to kneel in homage when Elizabeth became Queen in November 1558 and his reward was to become Secretary of State. "This judgment I have of you", she said, "that you will not be corrupted by any manner of gifts, and that you will be faithful to the state; and that without respect to my private will, you will give me that counsel which you think best."

Her word became a bond between them that was never broken during 40 years of loyal service to her cause. In 1572, he became Lord Treasurer and was raised to the peerage as the first Lord Burghley but to Elizabeth he was always

Sir Spirit, an incongruous and playful nickname for "the gravest and wisest counsellor in all of Christendom". The Queen was devoted to him, visiting him often at his home, and Cecil guided her through every crisis of her reign. When he talked of retirement, she refused to listen. "I need you old man", was her stock answer and so he continued to serve.

He became ill in the summer of 1598 and the Queen sent cordials every day and visited him as often as she could. Servants bringing him food were sent away and she would feed him herself. Cecil wrote to his son Robert: "Her Majesty, though she will not be a mother, yet showeth herself to be a careful nurse, by feeding me with her own princely hand." He died on August 5th at the age of 77 and for months afterwards, whenever his name was mentioned at meetings of the council, Elizabeth wept openly. It was a personal tribute to a Lincolnshire man with a political genius and someone who had showed a loyalty that has been unmatched in government since. |

See also

Faithful servant and trusted

adviser The Burghley Arms

Go to:

Main Index Villages

Index

|