|

The Eastgate plane

crash

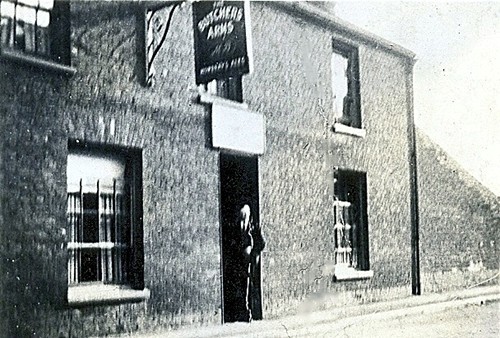

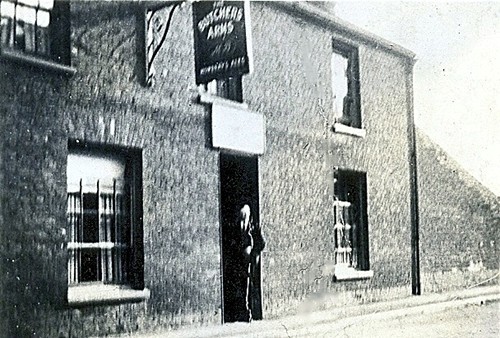

The Butcher's Arms in 1938 with landlord Charles Lappage at the door

A few minutes before midnight on

Sunday 4th May 1941, the people of Bourne were woken by the sound of

gunfire and the throb of aircraft engines as two planes battled it out

over the town.

World War II had broken out 18 months before and the German Luftwaffe was

engaged in a massive bombing campaign against sensitive British targets in

the industrial cities such as Sheffield, Birmingham and Newcastle. On this

occasion, a German Junkers 88 was bound for the East Midlands, probably

Grantham which was home to the Aveling Barford and

B-Marc munitions

factories, both producing weapons and other military equipment for the

armed services, when it was intercepted by a Royal Air Force Bristol Beaufighter and a dog fight ensued.

The Junkers loosed a number of incendiary bombs over the town but they

failed to inflict any damage and after several minutes of combat, with

flashes of machine gun fire lighting up the night sky, the Junkers was

badly damaged and the pilot injured and the plane nose-dived earthwards

with flames streaming from the fuselage.

It crashed on the Butcher’s Arms alongside the Bourne Eau at No 32

Eastgate, demolishing the public house, setting fire to the ruins and

killing seven people inside.

They included the licensee, Charles Lappage and his wife Fanny and two

relatives, Mrs Lappage's sister, Mrs Violet Jackson, and her daughter, Mrs

Minnie Cooper, who were also staying in the house, and an army officer and

a soldier who were billeted there although a third soldier died later from

his injuries.

THOSE ON DUTY

Les Jackson, aged 18, was fire watching at the premises of T W Mays and

Sons Ltd in Eastgate and was standing at the end of Willoughby Road

talking to others on duty when they heard the aircraft’s engines. In 1998,

then aged 76, and living in Stanley Street, he recalled that night. “The

aircraft appeared to be coming in from the coast”, he said. “Somebody said

it sounded like one of ours but then the cannons opened up and bits of

fuselage started falling all around us but we could not see a thing

because it was pitch black.

“We realised by the sound that the plane was in trouble because the engine

appeared to be going up and down like a yo-yo. We reckoned that the pilot

had been shot and the rest of the crew were trying to get him away from

the control so that they could take over but they didn’t succeed. Instead,

it went into a dive and the engines started screaming. It came down nose

first and must have been dropping at a terrific speed. We thought at first

that it had come down on the recreation ground, about a hundred yards

away, but it was far closer than that. I walked down towards the slipe

[the South Fen] and saw a parachute in the road and next to it one the

crew lay dead. I then went down Eastgate and saw what had happened.

“It was like nothing I had ever seen before. There were bodies all over

the place. The plane had sliced the pub away from the row of houses as

clean as a whistle. You would have thought it had been done by the

builders. The aircraft had gone straight through the building and the

engines had gone right into the ground for about 25 feet. The whole area

was covered in some sort of de-icing chemical and the smell from it was

terrible.

“I ran to the police station in North Street to get help and was quite out

of breath when I got there and worse still, when I told them that a plane

had come down in Eastgate and there was dead lying all over the place they

didn’t believe me at first. The inspector on duty said ‘You’re bloody

dreaming’ and so I told them to come back and see for themselves.”

Mr Jackson, who later served with the 11th Armoured Division in France and

Germany, added: “I remember the events of that night in every detail. It

was a very nasty experience. It was my first taste of war and you don’t

forget things like that. I had never seen a dead man before and I kept

thinking about it for weeks afterwards.”

A Home Guard unit was stationed at the Ship Inn, Pinchbeck, and at 11.30

pm, the duty guard saw the flashes of light from the dog fight over

Bourne, ten miles away. Private Tom Bray, aged 20, entered in the unit’s

report book: “Plane seen to fall in flames after two short bursts of

machine gun fire, west of guard point. Heavy detonations west to

north-west, intermittent flashes.”

Among those first on the scene was Ernie Robinson who was on duty with a

team of volunteers from the town's Civil Defence unit based at the Old

Grammar School in South Road that had been specially trained to deal with

air raid casualties. In 1998, then aged 97, he recalled the scene when

they arrived: “We heard the plane coming down”, he said. “It was only on

the other side of the Abbey Lawn and so we did not have far to go and we

turned out immediately.

“It was a shambles, a real mess. Soldiers from the Loyal Regiment were

billeted in Eastgate and one of them who had been on guard duty had been

killed. There was not a lot we could do to help and it was really a case

of clearing up as best we could. We found two of the German aircrew and

carried off their bodies to the stables behind the Six Bells public house

in North Street. The police station was next door in those days and they

took over as soon as we arrived and we left them searching through their

clothing to find some identification. Bourne was usually peaceful during

the war years but it certainly was not on that occasion which turned out

to be one of the busiest nights of the war.”

CIVILIAN WITNESSES

Vera Bristow and her husband Roland were living with her parents at Walton

House, Eastgate, at the time of the crash. The house was just a few yards

away from the Butcher’s Arms and although the property was not damaged,

telephone wires just six feet above the roof were slashed by the plane as

it came down. Sixty years later, in October 1998, Vera, then aged 80, and

Roland, aged 81, then living in Harvey Close, Bourne, relived the

experience. Roland was on war work at the B-MARC arms factory in Grantham

which made the machine guns for RAF fighter planes and when the cannon

shots began bursting over Bourne that night he was able to identify the

interceptor plane from the sound of its guns.

“We had just gone to bed”, he said, “and once I heard the noise I could

tell it was a Bristol Beaufighter straight away. Then we heard the German

plane with its engines screaming over the rooftops. You can imagine the

noise as it came down. I will never forget it.”

They dressed quickly and went out into the street. “The Butcher’s Arms was

totally devastated”, said Vera. “Most of it had been knocked into the

river and the entire aircraft was buried in the rubble with green fuel oil

running down the road. The smell was quite awful.”

Other soldiers staying at the public house had been injured and Vera took

them back to their home, bandaged their wounds and gave them mugs of hot

tea.

Stephen Hare, aged 22, who was home on leave from the RAF and staying with

his grandmother at her house in Hereward Street, Bourne, saw the plane

come down from his bedroom window. “I was woken by a burst of gunfire

followed a few seconds later by another”, he said. “I looked out of the

window and couldn’t see anything except what I thought was a shooting star

flashing across the night sky. Then all of a sudden I realised it was a

plane. It did not appear to lose height at first but then suddenly started

to fall although I had no idea where it had come down.”

Within minutes, residents living nearby began milling about the streets,

some who had hurriedly dressed while others were wearing pyjamas and

dressing gowns, all trying to find out what had happened.

Albert Bull, aged 19, was a nephew of the landlord, Charles Lappage, and

lived nearby at No 57 Willoughby Road. “That night, we heard the bullets

exploding and I was told later that the RAF plane had chased the bomber

all the way from Hull”, he recalled in 1998. “We went out into the street

as soon as we heard the crash and the police told us what had happened.

They had already cordoned off Eastgate and were stopping anyone going

through but when they realised that my mother Annie was the landlord’s

sister, they let us through. Mum was in tears and very upset and I tried

my best to comfort her but it was a very difficult time.”

Mrs Kathleen Ferguson, then aged 18, was living with her parents, Florence

and James Hanford, in Eastgate, just three doors away from the public

house, and they were woken by the commotion overhead. “We saw the planes

from our back bedroom window and when it crashed, all hell broke loose”,

she recalled later. “Soldiers started banging on our doors telling us to

get out in case there were unexploded bombs on board and when we got into

the street there was fire and rubble all over the place. We just did not

know what was happening. It was a most terrible experience.”

THE AIRCRAFT INVOLVED

|

|

|

|

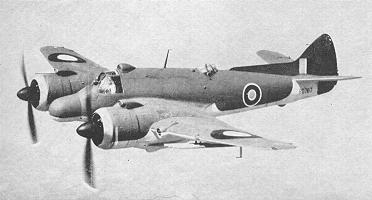

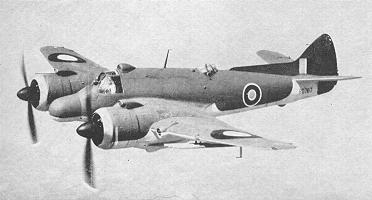

The Junkers 88 (left) similar to that which

crashed on the Butcher's Arms and the Bristol Beaufighter (right)

which shot it down after an aerial fight over the town. |

The Junkers or Ju 88 was one of the most important and versatile German

aircraft of World War II, having been developed by the Luftwaffe for every

kind of combat role, including dive bomber, night fighter, day

interceptor, photo reconnaissance, tank destroyer, and even as a

pilot-less missile, the forerunner of the flying bomb. The Ju 88 made its

first flight on 21st December 1936 and hundreds were still in use when the

war ended in 1945.

The Bristol Beaufighter was first used by the Royal Air Force in April

1940 as a high performance night fighter equipped with airborne

interception radar and successfully operated against the German night

raids in the winter of 1940-1941. It was later used by Coastal Command as

a strike fighter when the original formidable gun armament was retained

but rockets and torpedoes were added giving it an even greater fire power.

Not only did the Beaufighter operate with distinction in North West

Europe, but also a considerable reputation was earned in the Middle and

Far East.

THE GERMAN CREW

The Junkers had a crew of four and three of them baled out but two were

killed when their parachutes failed to open and their bodies were found

some distance away. The pilot, Adam Becker, aged 28, had remained at the

controls and was buried in the wreckage of the inn where the aircraft had

embedded itself in the foundations. The other two who lost their lives

were Reinhold Kitzelmann, aged 22, radio operator, and Karl J Focke, aged

22, observer.

A third crew member, the rear gunner, Rudolf Dachsesel, survived. He

landed by parachute south of the town near Northorpe and was slightly

injured but gave himself up to the Home Guard next day after walking into

Bourne along South Road. He later returned with a police escort to recover

a revolver he had hidden at the roadside a few yards from Baldock’s Mill.

The escort included Constable Ron Jarvis who was based at the police

station in North Road, Bourne, from 1939-41 and had helped to clear the

rubble from the crash site. “The airman told us that as soon as the plane

was hit, he pushed his guns out and decided to follow them”, he recalled

in 1998. “We put him in the cells but he was not with us for long before

an army unit arrived and took him away.”

The body of the pilot, Adam Becker, was found after extensive digging by

the rescue services and all three of the bomber crew who had been killed

were buried in the town cemetery at Bourne the following Thursday after a

short graveside service conducted by the Vicar of Bourne, the Rev Charles

Horne. In 1959, the War Graves Commission arranged for their exhumation

and reburial at the war memorial cemetery at Cannock Chase in

Staffordshire.

Engineering experts from the Ministry of Defence arrived next day and

removed what was left of the aircraft for workshop examination but they

did not recover everything and it is believed that one of the engines and

other parts of the wings and fuselage still lie on the bottom of the

Bourne Eau.

THE ROYAL AIR FORCE CREW

Although they completed a successful mission in shooting down a German

bomber, the crew of the Bristol Beaufighter took no pleasure in the

incident because of the subsequent loss of life and property. Flight

Lieutenant John Hunter-Tod was the plane’s radar officer and navigator and

in 1993, he wrote to Roland Bristow explaining their feelings. In May

1941, he was serving with No 25 Squadron (Beaufighters) based at RAF

Wittering, near Stamford, and flying with the commanding officer, Wing

Commander David Atcherley, at the controls. The Beaufighter had been

specially fitted with radar to enable it attack Luftwaffe bombers on their

nightly raids over Britain.

Hunter-Tod, then living at Dartmouth, Devon, said in his letter to Mr

Bristow: “I remember the event quite well although some of the details are

now a bit hazy. The morning after the incident, we went to Bourne in a

staff car to see our victim, not realising that we had scored an own goal.

What we saw certainly took the gilt off the gingerbread and we tactfully

withdrew. I knew that several soldiers billeted at the pub had been killed

but not that the place had been obliterated. What a shambles! You were

lucky not to have had the Ju 88 landing on you.”

David Atcherley (1904-1952) was commissioned in the RAF in 1927 and served

with distinction, becoming a legend in the service with his twin brother

Richard and achieving the rank of Air Vice Marshal. He was awarded the DFC

(1942), the DSO (1944), the CBE (1946) and the CB (1950) shortly before he

died.

Sir John Hunter-Tod (1917-2000) was commissioned in 1940, serving with

Fighter Command and in the Middle East, and after a notable war record,

had a series of important defence posts, being promoted Air Marshal in

1971 before retiring in 1973.

THE VICTIMS

|

The landlord and his wife were killed in

the crash. They were Charles Edward Lappage, aged 63, and his wife Fanny

Elizabeth, aged 59, who had been running the public house for ten years.

Mr Lappage was born in Bourne but when he left school, he moved away to

work for an engineering firm in Grantham where he met and married Fanny

but gave up his factory job after a bout of pneumonia and they moved back

to his home town in 1931 to take over the Butcher’s Arms. He was a quiet

but reliable man and devoted to his family and the couple enjoyed running

the pub but were beginning to talk about retirement. They had one son,

George, who had married Eva and were living in Grantham.

Also killed were two relatives who were visiting, Mrs Lappage's sister,

Mrs Minnie Gertrude Cooper, aged 62, and her daughter, Mrs Violet Frances

Jackson, aged 29, who had only been married for a fortnight. Her husband,

George Jackson, from Hull, had been serving as a fitter with the RAF at

one of the nearby air bases when they met and married just a few days

before his unit

embarked for Egypt. |

Charles and Fanny Lappage with young

son George |

The soldiers who were killed were all serving with the Loyal Regiment

(North Lancashire) which was based at Grimsthorpe Castle from 1940-41 with

tented accommodation in the grounds although some platoons were billeted

at various locations throughout Bourne, including Eastgate.

They were Lieutenant Harold Schofield, aged 28, Private Harrison Mackean,

aged 33, and a Welshman, Private Clifford James, aged 29, who was fatally

injured and died in hospital at Sleaford a few days later. He was a

regular soldier who had served in India and Palestine and had even

survived Dunkirk. Six other soldiers were hurt in the incident but all

recovered from their injuries and returned to duty.

One of their colleagues, Private John (Hank) Hankinson, who was also

billeted in Eastgate for a time, remembered the incident in November 1998

when he was 81 and living at Worsley, Manchester. “We all made many

friends in the town during our stay and certainly livened the place up at

weekends”, he said. “There were one or two regimental bandsmen with us and

they used to play for dances at the Corn Exchange on Fridays and Saturdays

and they were always popular events. The people were really nice and

friendly, especially some of the girls, and many long term relationships

were formed.

“The loss of Taffy James affected us most because he was a real old

soldier who had seen much service, a very witty chap and a noted character

in the regiment who was known and liked by everyone.”

A month after the tragedy, the Loyal Regiment moved out of Bourne bound

for North Africa where it fought with distinction in the desert campaign

against Rommel’s Afrika Corps and one officer won the Victoria Cross,

awarded posthumously.

THE PUBLIC HOUSE

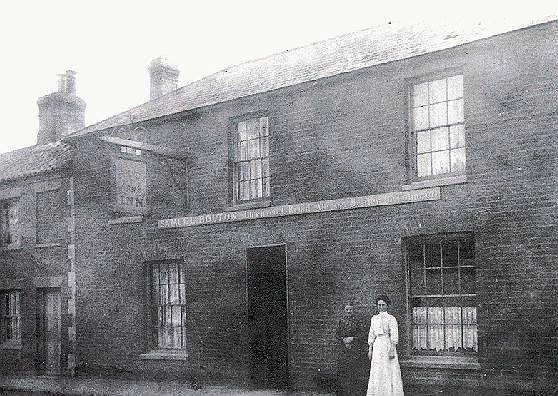

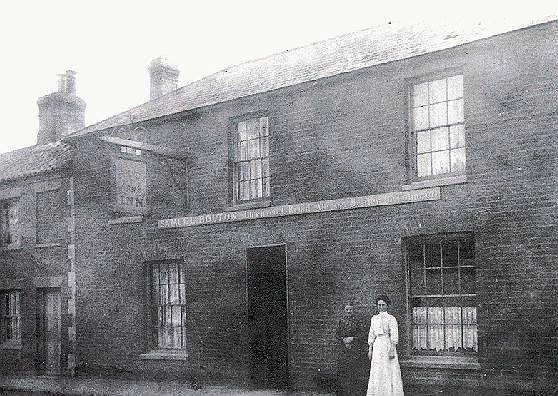

The Butcher’s Arms in Eastgate was built of brick and blue slate and dated

back to the early 19th century although there was probably a beer house on

the site prior to that. It became a popular drinking place for fen farmers

and agricultural workers, particularly between 1885 and 1913 when the

licensee was Samuel Bolton because he also farmed in North Fen and so

crops and the weather was a regular topic of conversation. Later, during

the early years of the 20th century, it was patronised by men working at

the Hereward Labour Camp that was established in Bourne to help ease the

national unemployment crisis.

The licensee when this photograph was taken

of the Butcher's Arms between

1885 and 1913 was Samuel Bolton, who also farmed in North Fen, and the

two ladies posing for the camera appear to be his wife and daughter.

Many of them came from the north of England

and they started using the pub after discovering that it served their

favourite mild beer at 4d. a pint. During the Second World War it became

the local for soldiers billeted at houses in the Eastgate area and

sergeants from the Loyal Regiment commandeered the front sitting room as

their mess while visiting officers and padres were often given

accommodation during their stay.

INFORMING THE RELATIVES

One of the most difficult duties for the emergency services in times of

disaster is in informing relatives of what has happened. The next of kin

of soldiers who were killed were officially told by the military

authorities according to a set procedure, often by letter, but it was the

task of the police to contact families of those civilians who had lost

their lives and this usually involved a personal visit. Charles and Fanny

Lappage had a son, George, who was living in Grantham with his wife Eva

and their two children, Trevor and Joan, and therefore he was the first to

be contacted with the tragic news.

George died in 1987 aged 76 but in October 1998, Eva, then aged 82,

recalled the dramatic events of that fateful night. There was an air raid

on Grantham that night and the family had just gone to bed after the all

clear had sounded when there was a knock at the door.

“Two policemen stood outside”, said Eva, who answered. “They said: ‘Would

you mind going inside and sitting down. We had some bad news for you.’ The

crash had only happened a short time before and they were unable to say

exactly what had happened although it did involve George’s parents and the

Butcher’s Arms. We dropped Trevor off a friend’s house and took Joan with

us and hired a taxi to take us to Bourne but halfway there a wheel broke

and it took so long to repair that it was dawn before we finally arrived.

“The taxi got to Eastgate and there were crowds milling about at the end

of the street but the police were not letting anyone through until someone

shouted ‘Here’s Mr and Mrs Lappage’ and we were escorted to the scene of

the crash and I saw what had happened. All you could see was the tail end

of the plane sticking out from a pile of rubble and the wreckage was still

smouldering. It was a horrible sight and one that I have never forgotten.”

She and George retrieved a few items from the ruins including Charles’

watch chain that Eva still wears as a necklace. But there was little else

they could do and after a few hours visiting friends, they returned home

to Grantham. Coincidentally, they had been due to visit Bourne for the

weekend but had called off the trip at the last moment. "Had we gone, we

too would have been killed", recalled Eva. "The irony was that both Minnie

and Violet also lived in Grantham and had gone to Bourne as a respite from

the bombing because the town was a target as a result of the munitions

factories based there."

A joint funeral was held in Grantham later that week for all four of the

family who died in the crash and all are buried in the town cemetery.

|

|

|

|

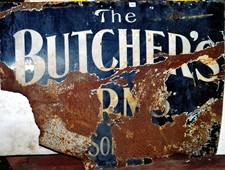

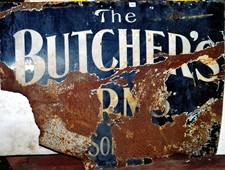

The remains of the public house sign which

was salvaged by Jack Lovell who years later hung it in his garage

that was built on the site of the plane crash. |

THE AFTERMATH

During the war, salvage teams had no time to retrieve debris after such

incidents and so the hole was filled in and the site of the Butcher's Arms

levelled. It remained derelict until after the war when it was bought for

a garage development by the late Jack Edmund Lovell (1929-2005) of

Riverside Motors which opened in 1959.

Five years later, in August 1964, he was expanding the business with

the installation of new underground petrol storage tanks and a JCB was

brought in to dig the necessary holes to accommodate them. A small crowd

had gathered to watch the work proceed and there was much talk of the

bomber crash which was still fresh in many people’s minds.

Digger driver Derek Bowers, aged 27, was at the controls and once his

machine began to excavate the site, fragments from the plane and even

machine gun bullets were being unearthed. The machine then struck

something more substantial and made of metal. “I hit it with the bucket”,

recalled Derek in later years. “I thought at first that it might be a

wheel from the undercarriage and I began hammering away in an attempt to

move it but it wouldn’t budge. Somebody went down into the hole to have a

look – I think it was Bill Darnes – but he got out pretty quickly when he

realised it was a bomb.”

The digger had in fact unearthed a 1,100 lb. unexploded bomb almost eight feet

below the surface that had buried itself so deeply in the ground that its

presence was undetected when the crater caused by the plane crash had been

covered over and left 23 years before. The police were alerted and they

called in a bomb disposal expert but a preliminary investigation revealed

that it was not likely to explode although the area was cordoned off for

the night and residents in Eastgate spent many anxious hours fearing that

it might explode and some even went to sleep with friends and relatives as

a safety precaution.

The following morning at 3 am, a squad arrived from RAF Newton near

Nottingham and loaded the bomb on to a lorry and took it away for

disposal. The officer in charge said that it was still "live" in that it

still contained its high explosives but it was "safe" in that the fuses

were not energised. The excavations also unearthed two clips of live

ammunition, electrical wiring and a fuel pipe from the aircraft.

Jack Lovell said afterwards: “A few of our older residents who remembered

the crash turned out to watch the excavations half-expecting us to find

something and they were not disappointed. What they did not realise was

that the bomb would have blown the street up if it had gone off. I would

not be surprised if there were a few more bombs down there still.”

He was only 13 at the time of the plane crash and living in the Austerby

but he joined dozens of more curious boys who flocked there on the Monday

morning to witness the devastation. “We went there looking for bits of the

aeroplane and even bullets as souvenirs”, he said. “One thing I did get

was the original sign from the Butcher’s Arms which was badly damaged and

I hung it in the garage after it was built as a reminder of that terrible

night.”

NO MEMORIAL

After Jack retired from business, the garage was demolished in 2001 and

new homes built the following year now occupy the site but there is no

indication of the tragedy that occurred there more than half a century

ago. Memories of the disaster were revived in 1998 when the Stamford

Mercury launched a campaign to provide a lasting memorial to those who

died, both German and British, in order that the younger generation might

be reminded of the conditions that existed during those wartime days.

The Mayor of Bourne, Councillor Don Fisher, gave his full support to the

idea and although he himself was not a resident at the time of the crash,

he felt it was an important event in the town’s history that should be

commemorated. He told the newspaper: “There are still many people in

Bourne who witnessed the event or went to look at the scene of the

disaster afterwards and therefore it should be remembered as part of the

consequences of the war to this town and one that came as a tremendous

shock to the community.”

There was also support from members of the Lappage family and the design

for an engraved plaque to be financed by public subscription and placed in

the Abbey Church was contemplated but despite an intensive campaign by the

newspaper over several weeks, interest waned and the idea of a memorial

came to nothing.

|

|

|

Jack Lovell's garage (above) on the site of

the former Butcher's Arms. It

was demolished 2001 and the site is now occupied by houses (below).

|

|

|

|

NEWS REPORTS

The plane crash was reported by the Stamford Mercury on Friday 9th

May 1941 but because of wartime restrictions on news coverage concerning

enemy action over Britain, the place name was not given to avoid divulging

information that might be of use to the enemy:

PLANE CRASHES ON

INN - ENEMY MACHINE BROUGHT DOWN

SEVERAL CASUALTIES

When a Junkers 88 was shot down over a town during the weekend, it crashed

into an inn and killed several of the occupants and injured another. The

crew of the enemy plane had loosed a number of incendiaries upon the town

which failed to do any damage, when a night fighter came up and shot it

down with a few short bursts of machine-gun fire. The 63-year-old

licensee, his wife and two relatives, Violet Frances Jackson and Minnie

Gertrude Cooper, who were staying in the house, were killed. An Army

officer and two soldiers who were staying at the house were killed and

another soldier was injured.

The Nazi plane was in flames as it came down and set the inn on fire, but

the local Fire Brigade and members of the civil defence services worked

splendidly in putting out the blaze and in rescue work. Of the plane's

crew, three baled out, but the parachutes of two failed to open and they

were killed. The other gave himself up. The pilot had remained in the

plane and was buried beneath the wreckage of the inn.

At the war’s end, when censorship of news reporting

was being lifted, the Stamford Mercury carried a story about the

extent of enemy air raids over the Bourne area and the public learned

officially for the first time about what had happened in Bourne and other

surrounding towns:

FULL STORY OF AIR RAIDS IN KESTEVEN

ONLY 29 PARISHES ESCAPE NAZI FURY

The full story of Kesteven’s suffering

under attack from the air throughout the years of war has been issued by

Mr F Coulson, county ARP officer, at the request of the county council.

The figures of casualties – 107 dead (mostly in Grantham), 96 seriously

injured – were given to the council three months ago, but there is much

detail in the present report that is new.

Four enemy aircraft crashed in our county: Junkers 88 came down at Bourne

(4 May 1941), at Market Deeping (22 June 1941), at Barrowby (11 October

1941), and a Dornier 217 at Boothby Graffoe (15 January 1943).

The crash at Bourne caused a serious incident resulting in loss of life.

The plane fell in flames at eight minutes before midnight on the Butcher’s

Arms, set it on fire, completely demolishing the building, and trapping a

number of people who were killed.

The plane, a total wreck, embedded itself in land below the foundation of

the house. A number of soldiers who had run from their billets were killed

and others injured. The fire prevented rescue parties working on the

building for some time and each time an attempt to move debris was made,

flames broke out afresh as the whole plane was drenched with petrol.

The death toll was seven killed and six injured. Of the four Germans in

the machine, two were found dead some little distance away, another,

slightly injured, gave himself up and the fourth died in the crash.

|

NOTE: Acknowledgments to the Stamford Mercury for its

reports on the incident carried in

October-November 1998 and to Mrs Eva Lappage and her son Trevor for

sharing

their memories and family photographs.

See also The man who dug up a

1,100 lb. bomb

Go to:

Main Index Villages

Index

|