|

Mass evacuation of boys and girls gets

underway in 1939 One of the

biggest movements of people caused by the Second World War of

1939-45 was the mass evacuation of children from sensitive areas

likely to be the target of enemy bombing attacks.

The policy was adopted in the light of the terrible devastation of

the civilian populations of Barcelona and Guernica during the

Spanish Civil War and the government wanted to avoid demoralising

servicemen with the news that their families had been killed in a

similar fashion while they were away fighting. Children in the

exposed industrial urban areas of the larger towns and cities were

regarded as being at risk because they lived in zones that included

munitions factories, railway and industrial installations, whose

destruction would reduce the nation’s war capability. Air raids on

them would therefore put people living in the vicinity at risk.

The war did not start until 3rd September 1939 but as early as

January and February that year, government appointed billeting

officers started knocking on the doors of houses, cottages and farms

in the safe rural areas, preparing a list of suitable accommodation

for the children should war break out. In May, every home in the

threatened areas received a pamphlet providing details of the

evacuation scheme and then when war became imminent, on the 1st

September 1939, there was a huge exodus of children from London,

Manchester, Birmingham, Liverpool and other industrial centres.

Over the next three days, 1,473,000 persons were moved from the

crowded cities of Britain, the majority of them children but there

were also mothers, teachers and escorts, and the entire operation

was completed without a single accident or casualty. They went by

road, rail and sea, with gas masks, identity labels tied to their

clothing and baggage and a supply of food for the journey. It was a

step into the unknown for all of them and many were frightened at

being away from their families for the first time.

The majority went to safe homes elsewhere in the country while

others were sent abroad, to America, Canada, South Africa or other

parts of the empire and between then and the end of the war in 1945,

the total had reached an estimated three and a half million,

although this figure has since been disputed and it may have been

much lower. Not all remained. Some children adapted happily to

country life, living with strangers, but almost all missed their

home surroundings and despite the dangers, many thousands returned

home while the sinking of an evacuee ship brought a tragic end to

overseas evacuation.

The original movement was a major undertaking but an efficient one,

despite the lack of modern day communications and computers, using

the old fashioned, operator controlled telephones and the postal

service, and when it was over, officials reported that “the children

behaved simply marvellously”. It was an exercise that was to be

repeated many times over in different places and at different times

before the war ended, but on a much smaller scale.

Among those cities that were evacuated was Hull, the east coast

fishing port where British shipping was a regular target for enemy

planes, and the children were sent to safety throughout the early

years of the war as it came under enemy attack. They were found

temporary homes inland in the Yorkshire countryside, at Soham in

Cambridgeshire and at Bourne where the arrangements for their stay

was in the hands of the Women's Voluntary Service [the WVS] which

established a network of 200 volunteers looking after the town and

28 of the surrounding villages which eventually provided homes for

900 of the evacuees, mainly from the Estcourt Street Board Schools

for infants and juniors in Hull and the Craven Street School for

juniors.

The lady in charge was Mrs Kate Cooke, the WVS chairman for the

area, who was subsequently awarded the MBE for her community service. She checked on the

available homes with her band of helpers, among them her teenage

daughter Joy, now living in Canada. “The children arrived with

labels around their necks, many quite distraught and lonely of

course”, she recalled. “They were magically taken into homes around

Bourne quickly although I never understood why they came to us as we

were on an obvious target ourselves if the Germans invaded. Many

were unhappy at being away from their parents and developed bed

wetting problems that distressed the people taking them in. I helped

a little, but being only 14 was not that valuable other than talking

and giving reassurance to some of the younger children and taking

them out for little walks, but in that situation, every little

helped.” Among the first to

arrive in Bourne from Hull on 1st September 1939 was Robert Mayo,

aged 4, and he was sent to live with Kath and George Rodgers at their

cottage in Spalding Road. The following month was his fifth birthday

and he was enrolled as a pupil at the Bourne County Primary School

[now the Abbey Primary School]. He stayed until 1946 and had several

other billetings in the town for short periods, with Harry and

Florence Barnatt in Stanley Street and at a children’s hostel which

was opened in West Street. But he looks back on the time spent with

Mr and Mrs Rodgers as the happiest in his life and in later years

returned regularly to see them and reminisce about the old days.

Although both are now dead, Robert, aged 70 and retired, still makes

an annual pilgrimage to Bourne with his wife Colleen to visit the

places he once knew and despite the deprivations and restrictions of

the war years where he was at his happiest.

On his last trip in August 2005, he recalled those times that had

become a landmark in the formative years of childhood:

I remember my stay in Bourne

as a period of beautiful summers and cold winters, kind-hearted

people, lovely food always on the table and everything was grown in

the garden. It was a very happy time and I loved every minute of it

and that is why I keep coming back. I had no idea why I had been

sent to Bourne because I did not understand the meaning of the word

evacuation and I didn’t know what the war was about until I got

older, but I soon came to realise that it meant a better life for me

than what I had been used to. At first, I did nothing but cry and

wet the bed, which is natural when kids are anxious and that must

have been difficult for these looking after because the lavatories

were so primitive, usually outside and made of wood and sometimes

even a hole at the bottom of the garden.

Schooling was alright. I was not a great scholar and not that well

educated but I did learn that two and two made four and I can look

after my cash perfectly well and practically, I can turn my hand to

anything.

But I loved being with Mr and Mrs Rodgers. My memories are of being

brought up to be well-mannered by them and after a while, I began to

regard them as my Mam and Dad and they took to me as their son and I

shall never forget as long as I live the kindness, the love and

tenderness they gave me. They were wonderful people and I was always

happy to be with them and when the time eventually came for me to

leave, I did not want to go and nor did Mrs Rodgers but the war was

over and there was no other choice and I had to go back to my own

family. Living here was the happiest and the loveliest time I have

ever had in my life. There

were however some experiences that Robert would like to forget. For

three months, while Mrs Rodgers was recovering from a difficult

birth, he was sent to live with one of the town’s prominent

businessmen who lived in North Road, then home to Bourne’s more

affluent citizens. “I try to blot those weeks out of my mind”, he

said. “Life was quite different for me in his house. Everything was

so strict and there was no consideration for children. My day ended

with bread and milk at half past three in the afternoon and I had to

be in bed by four even though all the other kids were still out

playing and enjoying themselves. He had this regime and kept to it

no matter how unhappy I was about it. That is something I will never forget from a man

who should have known better.”

|

|

|

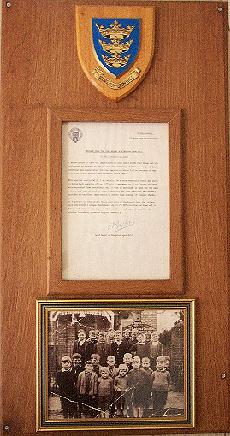

Some of the Hull evacuees pictured in

the playground at the county

primary school in Abbey Road,

circa 1943. |

There were other cases of cruelty and I have evidence of one boy

being similarly treated, also by one of the town's respected

businessmen who lived with his wife in West Road. He used to beat

the evacuee who had been allocated to his house with a golf club,

frequently locked him in the garage or in a cupboard and on

occasions made him drink his own urine. Eventually, the boy ran away

and started walking back to Hull but was picked up by the police but

when he told his story they refused to send him back to the same

house and he was billeted elsewhere. But these cases were rare and

most of the boys and girls who came to Bourne appeared to have

enjoyed their stay. David Collins, aged

5 (born 19th June 1935), was a pupil at the

school in Estcourt Street, and he remembers the air raids near his home

at 68 Rosemead Street, Newbridge Road, Hull, when he and his parents and eight brothers

ran for the aid raid shelter with bombs falling all around and

flames shooting forty feet in the air from the nearby church which

had been hit by several incendiaries. In later years, he recalled

that soon afterwards, he was evacuated to Bourne by train and went

to live with Walter Wade and his wife May at No 4 Hereward Street:

I called them Auntie May and

Uncle Walter and I cried my eyes out on that first night. I was only

a kid, no taller than the table top, but I was there for six years

and it turned out to be the most wonderful period of my life. I had

lots of love and memories, I went to a good school where I was

taught to read within the first few weeks. I became an altar boy at

the Abbey Church and later a choirboy, singing at services on Sunday

mornings and evenings and in the afternoons I went to Sunday School.

I can recall the many

airfields around Bourne, with both British and American personnel,

and after going on missions the damaged planes came through the town

centre on low loaders, all shot up and often in bits. But at

weekends, the flying crews would come into town for the Saturday

night dance at the Corn Exchange and to have a good time. The

Americans always handed out toys, sweets and cans of drink to the

evacuees once a year and they were always good for a packet of

chewing gum.

During the six years I lived

in Bourne I only ever saw my Dad once and I never saw my mother

until I went back to Hull when I was eleven years old. Auntie May

and Uncle Walter tried to adopt me but my parents would not hear of

it although had I been given the choice, I would have stayed in

Bourne because I was happy there. When I returned home, it was to a

house of strangers. People like Walter and May Wade deserve a medal

for all they did for the evacuees and the love they gave me.

There were other evacuations at regular intervals over the next

three years. Among them was Marjorie Spencer, then aged 13, who

arrived on 21st May 1941. “There were only three girls in our small

party”, she said, “and we all came from the Estcourt Street Board

School in Hull which was later bombed. We caught a train to Grantham

and then got the bus to Bourne and on arrival we were taken to the

Corn Exchange where the WVS ladies were waiting and we were

allocated our homes.”

She was billeted with local grocer Jack Smith and his wife Hannah at

their home in Mill Drove but soon became part of the family, staying

on after the war and she still lives in Bourne.

When the Estcourt Street Board School was destroyed during an air

raid in 1942, a large party of pupils arrived from Hull accompanied

by several teachers. They made the trip from Hull by bus to the

ferry that took them across the Humber, escorted by Royal Navy

patrol boats, to Immingham where they caught a train to Essendine,

on the main east coast main line, and then they were transferred to

a local train for the final leg of the journey to Bourne.

On

arrival, they were marched in a crocodile from the railway station

to the Corn Exchange where the WVS ladies were waiting and small

parties of children were then taken around Bourne to the various

homes selected by the billeting officer and the householders came

out and chose the children they wanted to live with them. By early

evening, most had been allocated a family and were settling

into their new homes while others were sent to Bourne House in West

Street, a large property that had been vacated by local solicitor

Cecil Bell in 1940 and bought by Kesteven District Council for use

as dormitory accommodation.

Bourne House which was used to house some of the evacuees

Another evacuee was Dennis Staff, aged 11, who was billeted with Ernest

and Lilian Grummitt at No 42 Burghley Street and his young brother

Gordon, aged only 5, went to stay with a family two doors

along while his elder brother Norman, aged 13, was allocated to a

family in West Road. “Mr and Mrs Grummitt’s son Maurice had joined

the Royal Navy and I was given his room”, recalled Dennis. “It was

all very strange at first but we soon settled in and looking back

now I realised that my time in Bourne changed my life for the

better.”

The boys and girls were soon participating in the life of the town.

Most of them attended the primary school but accommodation was limited and so overflow

classes were held in the schoolroom at the Baptist Church in West

Street which was taken over by Kesteven County Education Authority

in 1940 in order to create additional classroom space. The authority

paid an annual rental of £10 plus rates, heating and lighting costs

and the wages of a caretaker. The threat of aid raids meant that all

windows were blacked out to prevent lights from showing after dark

and a blast screen was erected in front of the two main windows in

the schoolroom.

Staffing also proved difficult but some teachers who accompanied

the children from Hull stayed on and resided in the town, among them a Miss Topham who

taught shorthand, typing and book keeping.

The evacuees remained until the war ended in the summer of 1945

although it was the early months of 1946 before arrangements were made for them to return home. But

their stay in Bourne had made a lasting impression. Some later

married local girls and had families while many others returned regularly to visit the

friends they had made. None forgot their wartime experience and many

remembered those days with satisfaction and even pleasure.

|

AN EMOTIONAL REUNION |

|

IN THE SUMMER of 1990, some of those who

had been evacuated to Dyke from the West Dock Avenue School in

Hull fifty years before arranged to make a return trip and they

came by coach for a tearful reunion. They arrived on Saturday

14th July to coincide with the annual fete to raise funds for

the village hall and the thirty visitors all turned up wearing

identity labels tied to their coats exactly as they had done

in 1940. They

were met by the Mayor of Bourne, Councillor Stan Pease, and

people from the village they had known and befriended. The

Lord Mayor of Kingston upon Hull, Councillor L A Taylor, sent

a suitable message from the Guildhall which was duly framed

and now forms part of a small display in the village hall to

commemorate the visit, together with a copy of his letter

which said: |

|

I am delighted to take the opportunity of

this visit by Mr Fred Stamp and his colleagues to express to

the village and community of Dyke a message of civic greetings

and appreciation for the hospitality shown to the evacuees of

the West Dock Avenue School, Hull, some 50 years ago.

This special reunion will, I am certain, be a very meaningful

event and serve to bring back memories of the difficult times

when our city's young children were separated from their

families. A debt of gratitude is owed for the warm welcome and

care offered to these youngsters and this important

anniversary provides an excellent opportunity to confer this

message of sincere thanks.

As a gesture to acknowledge those past acts of kindness I hope

the village will now accept a plaque which bears my City's

Official Coat of Arms and in doing so I also convey my

personal best wishes and appreciation for the genuine

friendship promoted by your community. |

|

In September 2004, Dennis Staff wrote an open letter to the local

newspapers to coincide with the 65th anniversary of the outbreak of

the war, thanking the town for its hospitality and

generosity. He wrote:

It is with deepest gratitude

that I thank you Bourne. You willingly opened your homes to dozens

of strange children from Hull who were frightened and afraid but it

was an enlightening experience that gave me confidence and

determination for the future. My evacuation to Bourne opened up a

new life for me, teaching many values which I still cherish, and I

am truly grateful to you all. I wonder how many people in Bourne

today would open up their homes and turn their daily routine into

chaos to provide a place of safety for strange children who spoke

with an odd dialect. It is only in my old age that I can appreciate

exactly the inconvenience they endured.

Dennis Staff had subsequently emigrated to Canada and

joined the Royal Canadian Navy where he had a distinguished career

as a naval intelligence officer, later seconded to NATO and working

for the Canadian government on the space shuttle. He retired to live

at Cumberland, Ottawa, the

Canadian capital, where he remained active with the Lions Club

International of which he became regional chairman. He died on 25th

February 2015, aged 82.

|