|

|

Watercress

days

by

JOHN STENNETT

|

I left Bourne Grammar School in 1953, looking forward to joining the Royal Air Force for my National Service when I was eighteen but I needed employment to cover the two-year gap. At that time, my father worked as general foreman at the railway station in Bourne and through his dealings with the traders who sent goods by rail, he came to hear of the various job openings that were going in the town. He eventually introduced me to the Spalding Water Company manager, Mr. Richardson, who supervised the watercress beds that were situated to the side of the Wellhead Gardens and the station field, and had in earlier times been owned by E N Moody and Sons Ltd.

I worked under the late Bill Barnes who lived in Ancaster Road and during the production season, men from the pumping station in Manning Road came to help out with the work and I remember that among them were Jack Latter, Jack Newton and Raymond Green.

After about six months or so, I changed employers and went to work for Moody's themselves. They had three locations growing

watercress and I worked at all of them, at Kate's Bridge, in Exeter Street and Harrington Street, the latter beds being between there, Recreation Road and George Street. The house in Harrington Street at its entrance belonged to Moody's and was occupied by their watercress foreman, Bill Walpole. The third man in our team was Jock Gray and we tended the three beds all year round.

In the period of my employ, we used water from artesian wells that had been specially sunk by the firm and this was diverted through the concrete-sided beds as a continuous running stream day and night. It was pure water of a high quality, clean and palatable, and we always filled our kettle with it to make the tea. We worked regular hours for most of the time, from 7.30 am until 4.30 pm, but during the harvesting season, we were always asked to work overtime, perhaps two hours on some good production days.

Throughout the year, we had to grow the watercress plants, fertilise them and use large wooden rakes to bash at the plants in the water, a tried and tested system of splitting them and forcing them to multiply and so increase production. Bashing them in this way generated broken plants that grew separate shoots and boost the crop through the new plants they produced. These rakes were about four feet wide with nine-inch pegs or teeth and were quite heavy for a young lad, especially when using one all day. We spent most of our time outdoors, apart from short breaks in the shed, and we wore rubber waders for most of the day and stood on wooden planks that stretched over the plants across the width of each bed. The depth of water was about 18 inches.

|

|

|

|

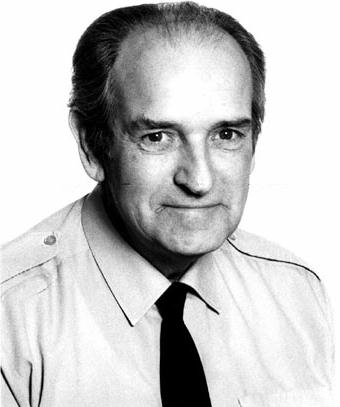

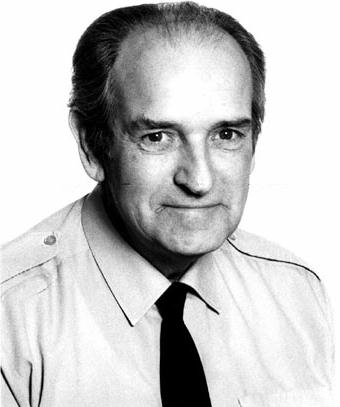

Cultivating and

harvesting watercress at the beds alongside the Bourne Eau behind

Baldock's Mill. These pictures, taken around 1953, show the cress

being divided with long rakes to produce a bigger crop (left) and

the watercress being cut and collected (right). |

In the springtime, the plants would flower and spread to a great thickness and shortly after flowering would come the cutting season. Cress was cut using long bladed knives and collected into bunches and we gauged a bunch size by using the thumb and forefinger and then secured them with rubber bands. We used to hold four bunches in the gaps between our fingers and thumb in either hand and then chop off the straggly stems at the end with a downward movement of the knife near the knuckle joints. This operation was always carried out near the flowing water tanks inside the shed and we wore rubber aprons and long wellies as a protection. We did not wear gloves because we needed to feel the produce to test for thickness of the bunches. It was also a very delicate and sometimes dangerous operation and I remember cutting one finger very badly but it happened only once and out came the sticking plasters. After that, I had learned my lesson and was more careful in the future.

When gathered, the cress was transported into a cleaning and preparing shed with flat wooden wheelbarrows. We often took some home for tea which was a very welcome meal because it was supposed to contain a lot of iron and was very good for you and sometimes we would have some in our lunchtime sandwiches. Ladies were employed during the harvest season to help pack the produce into punnets ready for transport to the railway station, where no doubt my father would be waiting to load the wagons. When our loads were ready at the beds, one of Moody's own lorries would go to all three beds to collect them and we would travel with the driver to help with the task of loading and unloading at each end. This was very hard work but most enjoyable. It was continuous but without having heavy loads to lift although we invariably got backache. I remember that in winter, we used to tie hessian sacks around our waists to help keep out the cold winds when breaking ice on the water beds.

This was my job between the ages of 16 and 18, working a 40-hour week for about 50 shillings (£2.50), which is equivalent to £40 a week today, although this would have increased to £5 a week if I had stayed on until I was 21 but by then I had joined the RAF. From those far off days I recall that Bourne watercress was transported to all the major markets throughout England including Covent Garden. Hard work, but happy and healthy times.

Contributed by John Stennett

(1938-2004) who

also supplied the photographs.

See

also Watercress

and flowers

Go to:

Main Index Villages

Index

|